Wood-fired stoneware

ABOUT THE ARTWORK

Who made it?

Peter Voulkos grew up in Bozeman, Montana. He attended Montana State College to study art in the late 1940s on the G.I. Bill after WWII. He began studying painting, but when he took a ceramics class, he found his life’s focus.

Voulkos was highly skilled on the pottery wheel—throwing pots and bowls and lidded jars and vases that were perfect in technique and form. These early works won him recognition and awards, but he soon found them and the process of making them unfulfilling. He said, “Technique is probably the most difficult tool to master, because it is a necessity, but can so easily become an obsession. Nothing can drown out new ideas as fast as an obsession with technique. Technique is nothing if you have nothing to say.”

While teaching a three-week summer course in 1953 at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, Voulkos met Josef Albers, Robert Rauschenberg, and John Cage—modern artists pushing the boundaries of what art could be through a variety of media. These artists and the Abstract Expressionists working in New York City at the time inspired and freed Voulkos to change the way he worked with clay. He began to push ceramics out of the realm of function and craft and into one where it was an expressive medium with sculptural potential.

What’s going on in this work?

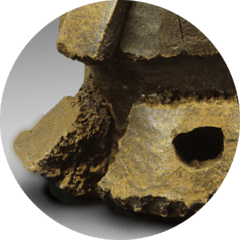

Voulkos was 77 years old when he created this sculpture during a week-long residency at the University in 2001 hence the title, Notre Dame. This sculptureis what Voulkos called a “stack” work (versus a plate or an “ice bucket”—the two other categories his works fall into), meaning that it was created by stacking a series of separately created pieces to create one cohesive work. The scale of his stacked sculptures (this work is over 4.5’ tall) required a substantial amount of physicality. Throwing the large individual component vessels, manipulating them with deep cuts and gouges, lifting the separate elements on top of each other, and attaching them firmly with punches and smashes all required a great deal of strength and left unique marks in the clay forms.

In Notre Dame, you can see this process from top to bottom in how the pieces were stacked and attached and from the inside out through the openings Voulkos cut into the piece. He made no attempt to hide his hand in making any of these marks. The gouges, tears, and impressions left by his fingers can be seen throughout this piece. His technique also gives us a glimpse into Voulkos as a human and as an artist. He often referred to his works as diaries—reflections of who he was as an artist and a human being struggling with challenges both lofty and mundane. He said that he could look at an early work and recall his particular state of mind at its creation.

Take a closer look.

Click on the full image of Notre Dame above to see a larger version of the work. Look closely at the sculpture and use these questions to guide your looking. Share your thoughts with your family, a friend virtually, or with us by responding to this email.

- What does this sculpture remind you of? What do you see that makes you say that?

- Voulkos was highly skilled on the pottery wheel, throwing plates, bowls, and vases with ease. Look closely at this sculpture. Where can you see these forms in this piece? What has he done to them to incorporate them into a “stack” sculpture?

- When something, like a clay vessel, is no longer utilitarian, what is it? What is its function now? If it can’t hold food or liquid, what can it hold instead?

To receive the collection in your inbox, join the Raclin Murphy Museum’s mailing list.

Engage with the Raclin Murphy Museum of Art by exploring their collection through background information and reflection questions. For more information on the collections, please visit the Raclin Murphy Museum of Art website.

Learn MoreJune 15, 2020