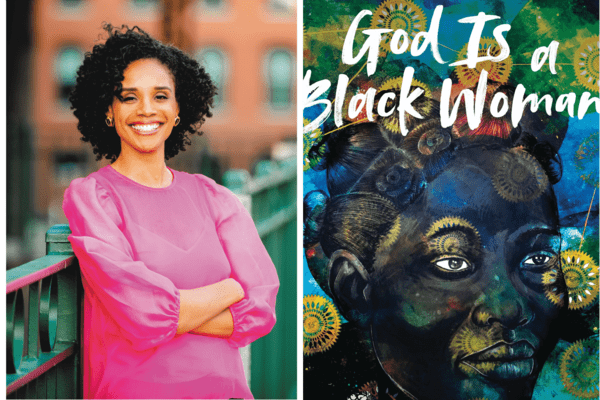

The final virtual event in the Medieval Institute’s Pilgrimage for Healing and Liberation series featured social psychologist, public theologian, author, and activist, Christena Cleveland, PhD, speaking about her 400-mile walking pilgrimage to the shrines of ancient Black Madonna’s. Cleveland is the founder and director of the Center for Justice + Renewal as well as its sister organization, Sacred Folk, which creates resources to stimulate people’s spiritual imaginations and support their journeys toward liberation. Cleveland’s talk was followed by an opportunity for questions from viewers. This event was moderated by LaRyssa Herrington, a 4th year doctoral student in Systematic Theology at the University of Notre Dame.

Cleveland began by reading the poem “The Maid” by Nayyirah Waheed to explain the concept of the sociological imagination. Cleveland pointed out, even when race is not explicitly named, we make assumptions about the racial identities of the woman described in the poem and of the family for whom she works, assumptions based on their class and access to power. Cleveland talked about her own awakening to the ways that the sociological imagination shapes one’s theological understanding of what is sacred and what is profane. After the murder of Trayvon Martin in 2012, and Trump’s election in 2016, she realized that Black life was not held to be sacred by Christians who imagined God to be white and male. Desperately seeking an image of the divine that affirmed the sacredness of Black women, Cleveland found the Black Madonna. An icon thousands of years old, venerated by people from all over the world, the Black Madonna became for Cleveland what scholar-activist bell hooks called “an icon of resistance” that affirms “the sacredness of all people, including all Black women, including Black trans women” (20:00).

There are about 450 Black Madonna shrines in the world, many bearing names connected to bodily vulnerability. Cleveland mentioned a particular Black Madonna known as “Slave Mama,” a figure “in solidarity with people who are physically in chains” (27: 25). Encountering the Black Madonna invited Cleveland to work on decolonizing her body, connecting her head with her heart, and practicing mindfulness to listen to the voice of her body. This work sparked her desire to make a pilgrimage to visit Black Madonna shrines. Cleveland wanted to be in the presence of this sacred image. In 2018, she visited 18 Black Madonna shrines in the Auvergne region of France. One of these, “Our Lady of the Sick” in Vichy, France, dates to the 1300’s. During the French Revolution, her body was destroyed by revolutionaries, and only her head was salvaged. For Cleveland, this history resonates with “the way that colonialism and white supremacy and patriarchy have disconnected my heart and my body from my head” (34:37). By making the pilgrimage, Cleveland wanted to reconnect with her body and with the land, and to heal from the “ways that Black women’s bodies have been disconnected from the land” (34:50). Cleveland cited Kelsey Blackwell’s book, Decolonizing the Body, which describes colonization as “dismemberment.” The colonial program, writes Blackwell, “makes us forget the power, wisdom, and liberation residing in our own bodies, and it also erases the dignity of our ancestors” (36: 17). Standing before Our Lady of the Sick, who had been dismembered and “lovingly pieced back together,” Cleveland realized that she didn’t need to hide her own dismemberment. She didn’t need to be perfect to be valuable. This Black Madonna invites all people to come to her as they are and to create communities based on mutual nurturing.

Cleveland learned about Black Madonna’s that did not appear in her research by talking with people who had grown up in the villages. One of these was the twelfth-century “Our Lady of the Rock,” whom Cleveland nicknamed “Our Lady of the Side-eye” because she is looking askance at a white male priest kneeling next to her. Although Cleveland was not able to see this statue in person, her image affirmed that Black women’s anger and critique are sacred too. During the question-and-answer session, Cleveland explained that she understands the Black Madonna and Mary, the Mother of God, to be one and the same. Early Christian tradition depicted Mary as a Black or Brown woman. Sadly, Black Madonna images are rare in Black-majority countries today due to the legacy of white colonialism. Finally, Cleveland agreed that the practice of pilgrimage can support us in the work for racial justice and healing. “It’s in connecting to our bodies that the power of liberation lies” (58:55).