Laocoön and His Sons

ABOUT THE ARTWORK

Who made it?

In the late 17th and 18th centuries, the craze for Greek and Roman antiquities was so intense that some sculptors made their reputations restoring fragments of ancient sculpture or copying well-known models, like the Laocoön, rather than conceiving and executing original works.

The original version of Laocoӧn and His Sons is believed to have been a bronze sculpture created in the second century BCE by three artists, Hagesandros (or Agesander), Polydoros, and Athenedoros from the Greek island of Rhodes, as recorded by Pliny the Elder. A Roman artist in the first century CE produced a marble replica of the original bronze which survives today and may be seen at the Musei Vaticani. The Roman marble was rediscovered in 1506, triggering a resurgence of interest in classical sculpture and artworks inspired by Greco-Roman works. Wealthy patrons would frequently commission replicas of famous ancient works for their private collections, a trend that continued well into the 18th-century.

What’s going on in this work?

Laocoӧn and His Sons illustrate a scene from Virgil’s Aeneid (29–19 BCE), which describes the death of the Trojan priest of Apollo, Laocoön, and his two sons. According to the epic poem, when the Greeks delivered the Trojan Horse to the gates of the city of Troy in the hope of breaching their defenses, Laocoön attempted to warn the Trojans of the ruse saying, “Beware of Greeks bearing gifts.” The goddess Athena, who sided with the Greeks, sent giant sea serpents to kill Laocoön and his sons for their interference.

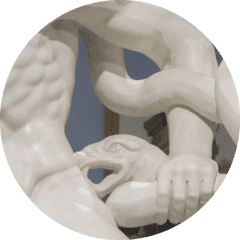

Many copies of Laocoӧn and His Sons have been made; this three quarter-sized one was probably made for a wealthy collector’s private home and advertised to all who saw it the owner’s superior taste and classical education. Though smaller in scale than the Roman marble, this version demonstrates the compositional aesthetic of the original—it is meant to be seen from the front (though all sides are visible), from only a short distance away. To learn more about this sculpture, watch this Insights from the Director video, or read our gallery handout, Echos of Antiquity in Eighteenth-Century Art.

Take a closer look.

Click on the full image of Laocoӧn and His Sons above to see a larger version of the work. Look closely at the sculpture and use these questions to guide your looking. Share your thoughts with your family, a friend virtually, or with us by responding to this email.

- What’s going on in this work? What do you see that makes you say that?

- The undulating serpent helps to move your eye around the sculpture by winding through and around the three figures. What other elements guide your eye through this sculpture?

- Sculptures like Laocoӧn and His Sons offer many clues to help to identify when they were made. For example, the marble used in this version was popular between 1650 and 1780 and was depleted by the early 19th century, later sculptures are whiter with a higher sheen. Here you can see drill marks in the locks of hair, a technique for determining the depth of the marble block, which was replaced by pointing machines after 1780. Zoom in on other parts of the sculpture in the large image, what textures do you find? What kind of tools might make marks like those?

To receive the collection in your inbox, join the Raclin Murphy Museum’s mailing list.

Engage with the Raclin Murphy Museum of Art by exploring their collection through background information and reflection questions. For more information on the collections, please visit the Raclin Murphy Museum of Art website.

Learn MoreJuly 6, 2020