Francis Place’s Ballads

View more in London in Song | Jack Hall

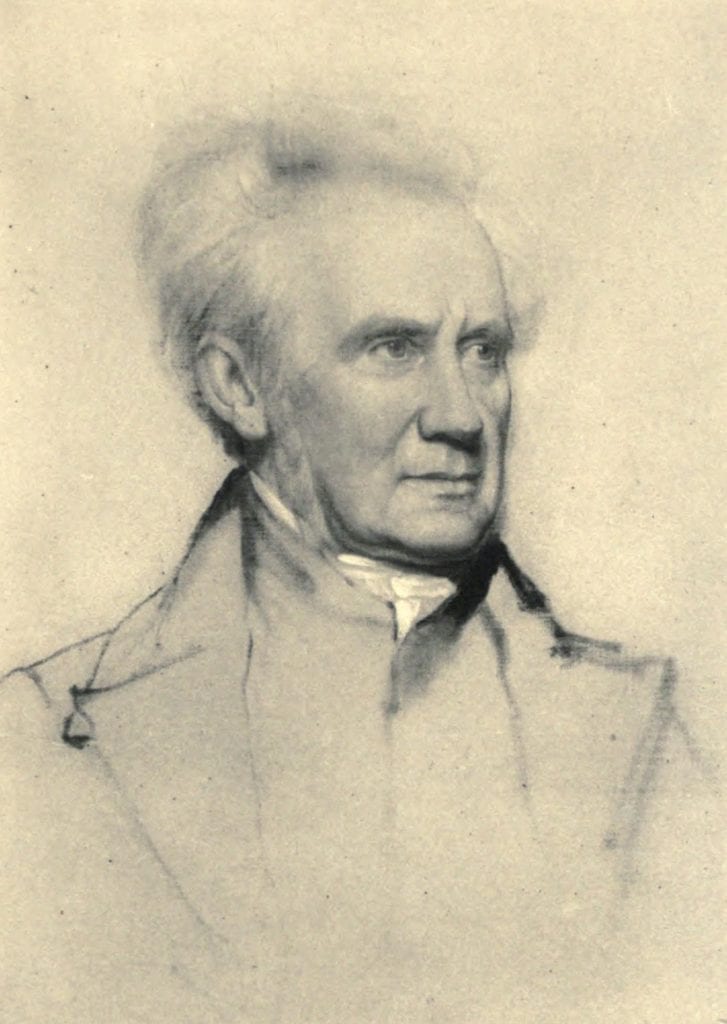

The first record we have of the existence of the ballad “Jack Hall” is in Francis Place’s collection of ballads that is now in the British Library. Francis Place was a successful tailor and important social reformer who lived between 1771 and 1854. He is best known for his contributions to the development of working-class rights, and he campaigned throughout his life for universal male suffrage, becoming an important figure linking the radicalism of 1790s London to the Birmingham Political Union and the Chartists. He also collected a vast archive of materials relating to the lives and experiences of ordinary working men and women in London. Among these voluminous papers is a collection of ballads that he wrote down from memory in consultation with some friends.

This is a collection of around thirty-six ballads that Place remembered hearing sung in the streets of London and that he wrote out from memory forty years later, around 1819, as evidence of what he understood to be the “improvement in the morals and manners of the working people” over that period. That is, these are ballads that he recorded specifically because they were evidence of the debauched and depraved behaviors of late eighteenth century London.

There are songs about drinking, such as “Drunk the Other Night.” There are songs about prostitutes, such as “The Whore’s Downfall.” There are songs about fornication, such as “A Hole to Put Poor Robin In.” And there are songs about theft, celebrating the exploits of notorious highwaymen such as Dick Turpin, Jack Chance, and Sixteen String Jack. Place claims that these ballads are typical of the songs that were ubiquitous on the streets of London in his youth but which by 1819 had been silenced. Some of the ballads are written out in full, some are half-remembered, some consist only of a notable line, but all have the qualifying distinction that they are in bad taste. “It will seem incredible that such songs should be allowed,” Place commented, “but it was so.”

It is among the ballads in praise of thieving that we have the first record of Jack Hall. And Place writes this:

One [song] which was made to the honour of some

notorious thief had these words, all I now remember

I furnished all my rooms every one, every one

I furnished all my rooms every one

I furnished all my rooms with mops brushes and hair brooms

Wash balls and sweet perfumes them I stole, them I stole

I sailed up Holborn Hill in a cart, in a cart

I sailed up Holborn Hill in a cart

I sailed up Holborn Hill at St Giles’s drank my fill

And at Tyburn made my will in a Cart

Place doesn’t remember the name of the song, or the name of the thief who was being celebrated, but we know that it was Jack Hall because a few years later a broadside ballad was printed that contained the words Place remembered with just a few variations. In this broadside version, the title of the ballad is “Jack the Chimney Sweep,” and the opening line is “My name it is Jack All chimney sweep, chimney sweep.” The H of Jack Hall has been dropped, suggesting that whoever transcribed this ballad had done so from the oral tradition, knowing it first through hearing it, before committing it to paper, just as Place did.

Place’s scribbled manuscript notes are the earliest evidence we have of the song’s existence. No one has been able to prove that the ballad definitely originated in the Tyburn Fair celebrations, as seems likely. But it does seem clear that the song existed for a while as part of the oral tradition before anyone wrote it down, not only on the evidence of the missing H in Pitt’s “Jack All,” but because of Place’s memory of it. Recall that his collection was made in 1819, but Place was remembering the song from the time he was an apprentice in the 1780s. So, it seems to have existed for at least forty years before it appeared as a broadside ballad, so why not another seventy years before that?

This is, of course, a perennial problem for scholars of early ballads. The paper trail of a song’s existence often has large gaps in it, and it’s hard to definitively prove things, so we have to rely on likelihood and possibilities. But the nice thing about the ballad “Jack Hall” is that, while its origins remain obscure, in the mid-nineteenth century it became very popular indeed, and we have a wealth of information to attest to the song’s popularity and its evolution. And this is what I’ll talk about in the next video.

2 minutes