Jack Hall

We begin with "Jack Hall," an old ballad that has its origins in the early eighteenth century. It begins as a narrative of the life of a convicted criminal who was executed at Tyburn Tree in 1707, but then mutates across time, with recordings by Irish and American artists like the Dubliners and Johnny Cash. We will ask what each of these versions contribute to the evolving tradition of the song, and how it became so widely known.

Meet the Faculty

Presented by Ian Newman

Ian Newman is a professor in the English Department and a fellow of the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies and of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies. He specializes in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Britain and Ireland, and has taught courses on spy fiction, satire, William Blake, literature and revolution, and literature and architecture. Professor Newman has recently published a book on eighteenth century London Taverns, and is currently working on a book on political ballads.

Tyburn Fair

Presented by Ian Newman

Jack Hall has its origins in the Tyburn Fair celebrations that occurred in London on the days when convicted felons were paraded around the streets before their public hangings.

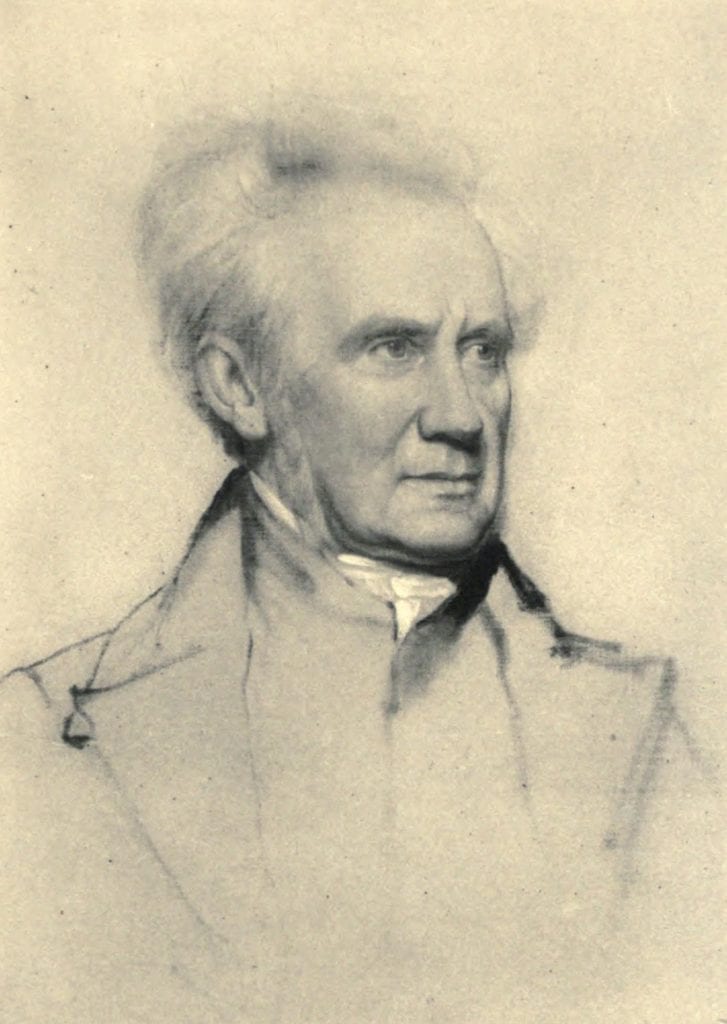

Francis Place's Ballads

Presented by Ian Newman

The first record we have of the existence of the ballad “Jack Hall” is in Francis Place’s collection of ballads that is now in the British Library. Francis Place was a successful tailor and important social reformer who lived between 1771 and 1854. He is best known for his contributions to the development of working-class rights, and he campaigned throughout his life for universal male suffrage, becoming an important figure linking the radicalism of 1790s London to the Birmingham Political Union and the Chartists. He also collected a vast archive of materials relating to the lives and experiences of ordinary working men and women in London. Among these voluminous papers is a collection of ballads that he wrote down from memory in consultation with some friends.

This is a collection of around thirty-six ballads that Place remembered hearing sung in the streets of London and that he wrote out from memory forty years later, around 1819, as evidence of what he understood to be the “improvement in the morals and manners of the working people” over that period. That is, these are ballads that he recorded specifically because they were evidence of the debauched and depraved behaviors of late eighteenth century London.

There are songs about drinking, such as “Drunk the Other Night.” There are songs about prostitutes, such as “The Whore’s Downfall.” There are songs about fornication, such as “A Hole to Put Poor Robin In.” And there are songs about theft, celebrating the exploits of notorious highwaymen such as Dick Turpin, Jack Chance, and Sixteen String Jack. Place claims that these ballads are typical of the songs that were ubiquitous on the streets of London in his youth but which by 1819 had been silenced. Some of the ballads are written out in full, some are half-remembered, some consist only of a notable line, but all have the qualifying distinction that they are in bad taste. “It will seem incredible that such songs should be allowed,” Place commented, “but it was so.”

It is among the ballads in praise of thieving that we have the first record of Jack Hall. And Place writes this:

One [song] which was made to the honour of some

notorious thief had these words, all I now remember

I furnished all my rooms every one, every one

I furnished all my rooms every one

I furnished all my rooms with mops brushes and hair brooms

Wash balls and sweet perfumes them I stole, them I stole

I sailed up Holborn Hill in a cart, in a cart

I sailed up Holborn Hill in a cart

I sailed up Holborn Hill at St Giles’s drank my fill

And at Tyburn made my will in a Cart

Place doesn’t remember the name of the song, or the name of the thief who was being celebrated, but we know that it was Jack Hall because a few years later a broadside ballad was printed that contained the words Place remembered with just a few variations. In this broadside version, the title of the ballad is “Jack the Chimney Sweep,” and the opening line is “My name it is Jack All chimney sweep, chimney sweep.” The H of Jack Hall has been dropped, suggesting that whoever transcribed this ballad had done so from the oral tradition, knowing it first through hearing it, before committing it to paper, just as Place did.

Place’s scribbled manuscript notes are the earliest evidence we have of the song’s existence. No one has been able to prove that the ballad definitely originated in the Tyburn Fair celebrations, as seems likely. But it does seem clear that the song existed for a while as part of the oral tradition before anyone wrote it down, not only on the evidence of the missing H in Pitt’s “Jack All,” but because of Place’s memory of it. Recall that his collection was made in 1819, but Place was remembering the song from the time he was an apprentice in the 1780s. So, it seems to have existed for at least forty years before it appeared as a broadside ballad, so why not another seventy years before that?

This is, of course, a perennial problem for scholars of early ballads. The paper trail of a song’s existence often has large gaps in it, and it’s hard to definitively prove things, so we have to rely on likelihood and possibilities. But the nice thing about the ballad “Jack Hall” is that, while its origins remain obscure, in the mid-nineteenth century it became very popular indeed, and we have a wealth of information to attest to the song’s popularity and its evolution. And this is what I’ll talk about in the next video.

The Cider Cellars

Presented by Ian Newman

“Jack Hall” was transformed into “Sam Hall” by the early music hall singer W.G. Ross, whose electrifying performances in the Cider Cellars of Maiden Lane in Covent Garden enraptured an entire generation.

Reading from GWM Reynolds' "Mysteries of the Courts of London"

Presented by Ian Newman

George WM Reynolds was the father of the so-called “Penny Dreadfuls,” a publishing phenomenon of the nineteenth-century. These serialized stories were published weekly, often over many years, adopting the tropes of gothic fiction to describe the poverty, violence, and crime of London. In one sequence, Reynolds provides us with a vivid description of W.G. Ross’s performance of “Sam Hall” at the Cider Cellars.

Read George WM Reynolds, Mysteries of the Court of London, “Recreations and the Horrors of London Life”

The Irish Tradition

Presented by Ian Newman

Listen to The Dubliners perform “Sam Hall,” available on YouTube, Spotify, and Apple Music.

When the Dubliners recorded “Sam Hall,” the title character had been transformed from a blaspheming felon, a victim of circumstances beyond his control.

The American Tradition

Presented by Ian Newman

Listen to Johnny Cash sing “Sam Hall,” available on YouTube, Spotify, and Apple Music

Johnny Cash’s version of “Sam Hall” reveals some important differences in the way the song was adopted in the American tradition.

View the Event

Presented by Ian Newman

Subscribe to the ThinkND podcast on Apple, Spotify, or Google.

Featured Speakers:

- Ian Newman, Professor in the English Department and Fellow of the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies and of the Nanovic Institute for European Studies, University of Notre Dame

- Rev. Jim Lies C.S.C., Senior Director for Academic Initiatives and Partnerships for the Notre Dame London Global Gateway, University of Notre Dame

Additional Resources

Presented by Ian Newman

- Spotify playlist of versions of “Sam Hall” or “Jack Hall”

- Mainly Norfolk is a wonderful resource for traditional song. Here’s their page on Jack Hall.

- The main catalog for English traditional song is the Roud Index, housed in the Vaughan William Memorial Library. Here’s the Roud Index entry on Jack Hall (Roud #369).

Prepare for Next Week

Presented by Ian Newman

- Read “The Waterman” by Charles Dibdin. Available online here.

- Listen to “The Jolly Waterman” by the Seven Dials Band. It’s available on Spotify, Apple Music, or YouTube.