The Forest and the Trees

Notre Dame research provides complementary angles on childhood adversity

Steven King, 7, builds a tower with Lego blocks at Notre Dame’s William J. Shaw Center for Children and Families while he tells family coach Rosemary Salinas about his scary dream.

Steven had awakened in the night and didn’t want to get back into bed because he thought a snake might be under the covers. It sounds like a common nightmare until his mother, Kathryn Kandzierski, clarifies that he did in fact have a small and harmless pet snake that had escaped earlier that day.

Salinas and Steven make exaggerated scary faces in response to this information. So Kandzierski steps in, asking exactly the type of question that Salinas modeled two years earlier during the Heart to Heart program designed by Kristin Valentino, the center’s director and an associate professor of psychology.

“How did that dream make you feel, Stevie?” Kandzierski asks.

He answers immediately: “Scared!”

Valentino believes that helping kids identify and express their emotions with their mothers helps children to develop emotion regulation and to improve the parent-child relationship. Her research is measuring whether sensitive and supportive discussion of these memories and emotions can be a buffering factor that helps the children overcome the adversity they have experienced, as well as prevent it from recurring.

Salinas beams with pride. The six-session intervention program teaches mothers of children exposed to adversity how to improve parent-child communication by asking open-ended questions that encourage kids to reminisce about past events in their lives.

IF VALENTINO’S PROJECT CONCERNS THE CARE OF A FEW HUNDRED TREES, THEN THE NATIONAL STUDY IS THE 30,000-FOOT VIEW OF THE FOREST.

“He’s a lot calmer than he was because he can express how he feels,” says Kandzierski, a certified nursing assistant at Holy Cross Village’s retirement facility. “Our relationship has changed. I’m more focused on the kids and less worried about household things. Rosie said you can always come back to housework. When he’s ready to talk, take advantage.”

Valentino’s goals are to evaluate how intervention can improve caregiving and to improve developmental outcomes for maltreated children. This effort directly addresses a serious problem in Indiana, which has about 700,000 child abuse victims each year, a rate that is double the national average.

Recent research has found that early adversity, including child abuse, can have lifelong negative health effects. Valentino notes that a study by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has demonstrated that an accumulation of adverse childhood experiences has measurable effects on individuals’ physical and mental health as adults, a crisis with a national price tag of nearly $6 trillion.

If Valentino’s project concerns the care of a few hundred trees, then the national study is the 30,000-foot view of the forest. And that is exactly the kind of research done by Sarah Mustillo, a sociologist and the I.A. O’Shaughnessy Dean of Notre Dame’s College of Arts and Letters.

As an undergraduate student at Notre Dame, Mustillo planned to become a doctor. She had trained as an emergency medical technician and worked that job throughout college.

“The more I worked in the medical field as a student, on an ambulance and in the emergency room, the more I became exposed to the social factors that influence health and illness, which was exciting,” Mustillo says. “I decided that instead of becoming a physician, and having an impact on a patient population directly, I wanted to study the risk factors that cause poor health.”

She began to study sociology and eventually focused on the intergenerational transmission of health and illness, earning master’s and doctoral degrees from Duke University. Studying how parents transmit health traits and habits to their children led to a transition into childhood adversity research, which she found fascinating.

“It’s not obvious,” Mustillo says. “You’re exposed to something traumatic when you’re 3 or 4. Really, that’s going to increase your risk of getting cancer when you’re 55? Yes, it does. To me, that’s a really interesting question to unpack. How does that happen? How does what you experience as a little kid translate into poor health when you’re an adult?”

Mustillo traces the origin of this field back to Dr. Vincent Felitti when he was chief of preventive medicine for Kaiser Permanente in San Diego. In 1985 Felitti was helping obese patients lose weight when he learned that a disproportionate number of them had been sexually abused as children.

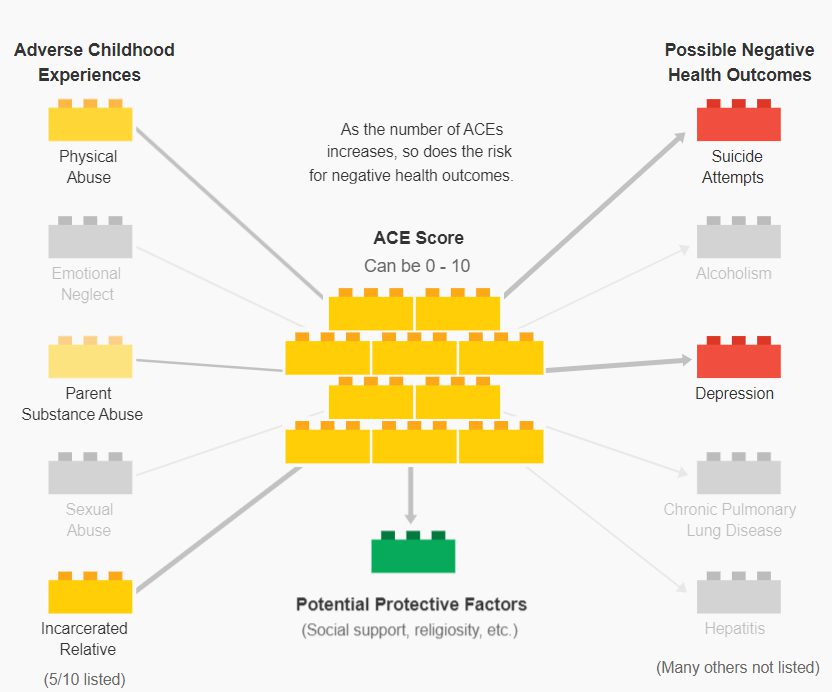

Over the years, this link between childhood trauma and adverse health in adulthood became more established, culminating in the CDC study on Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE). The study found, for example, that an ACE score of four or more increases the risk of hepatitis by 2.4 times, emphysema by 3.9 times, alcoholism by 5.3 times and attempted suicide by 12.2 times.

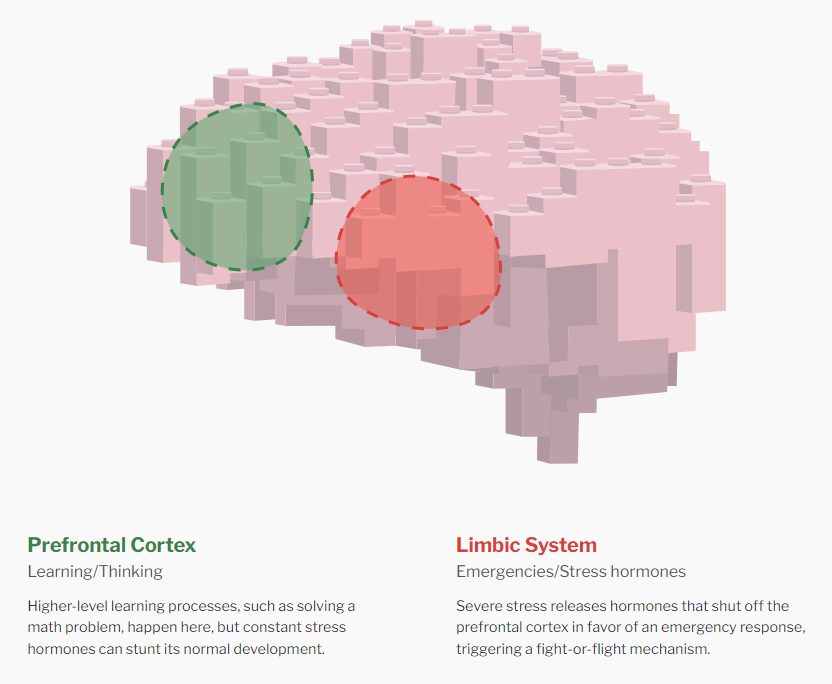

Parallel brain research provided the explanation for how childhood experiences land people in a hospital decades later. Severe or chronic trauma releases stress hormones — adrenaline and cortisol — that shut off the prefrontal cortex and trigger a fight-or-flight mechanism. That’s great for running away from a bear, but the hormones become toxic when they are turned on for too long, shutting out the normal learning process. Coping methods include conscious and unconscious decisions that lead to chronic health problems.

“There’s a large body of research on childhood adversity in sociology and psychology and medicine,” Mustillo says. “But the methods we are using are so basic they inhibit our ability to ask deeper, more meaningful questions about it.”

“Because this line of research started with physicians and spread to epidemiologists and psychologists and sociologists, it was very embedded in the substantive questions. Few researchers were thinking about the methodological questions.”

Mustillo studies substantive questions as well, but her latest paper in this subject focuses on the methodology of creating an ACE score. The cumulative score adds up negative factors, such as child abuse and parent drug use, to determine things like cancer risk.

Mustillo believed that this method was too simplistic because it treats every adverse experience as the same. Also, it did not account for “protective” factors such as social support, religiosity or mother-child communication like the Heart to Heart program, which have a positive impact on health.

Her recent article, “Evaluating the Cumulative Impact of Childhood Misfortune: a Structural Equation Modeling Approach,” aims to refine ACE scoring. It allows different adverse experiences to have different weights to measure how they affect different outcomes, and it also takes into account those protective factors.

Funded by the National Institute on Aging, the study analyzed data from 2004 to 2012 from the University of Michigan Health and Retirement Study, a longitudinal panel study that surveyed a representative national sample of adults 51 and older. Her analysis included nearly 6,000 participants.

Mustillo’s research proposes a new model that refines ACE scoring by allowing different adverse experiences to have different weights to measure how they affect specific outcomes. It also takes into account “protective” factors that have a positive impact on health.

Mustillo says she hopes that this new approach will help field researchers like Valentino.

“She’s working on the protective factors in my study, working with mothers to teach them how to be better parents, how to be more supportive, to try to offset having a negative outcome in the future,” Mustillo says. “Because it’s an intervention study, she meets with the families and knows them. That’s a very different study from what I do.”

In fact, Mustillo says it would be unethical for her to know the subjects in her nationwide, longitudinal studies.

At the opposite end of this spectrum, Valentino and her family coaches get to know the families in her project quite well. She says her research shares a similar “overarching model” with Mustillo’s: “to understand how childhood adversity leads to poor outcomes later in life.”

“The dean’s research is methodological in approach and offers a new way for the field to think about and test hypotheses about how specific types of adversity may affect long-term outcomes for children’s health,” Valentino says. “It also gives us a more precise way to model the effects of individual protective factors and how they can buffer against adversity to support a child’s health.”

Valentino says broad longitudinal data allows the researcher to observe and identify patterns that can’t be detected in small samples. And randomized clinical trials allow researchers to evaluate precise mechanisms further through experimental manipulation.

“Both are important for advancing theory and how you can translate that theory into practical applications that can improve kids’ lives,” she says. Taken together, a clearer view of the forest and the trees emerges.

“THE WHOLE GOAL OF MY INTERVENTION IS TO IMPROVE MATERNAL SUPPORT.”– Kristin Valentino

In college, Valentino took a developmental psychopathology course that assigned her to mentor a young boy with an extreme history of abuse and neglect. Since then, she has pursued research questions that would make a difference in his life, and she now teaches a similar course focused on children in the foster care system.

Because 90 percent of abuse is by parents, and 80 percent of kids remain in their custody, the Heart to Heart program was designed to intervene early — kids 3 to 6 in age. The program had 240 participants, including a control group not involved with maltreatment.

Valentino says there were already strong programs for infants and for older children. “I wanted to address this gap by developing a brief intervention focused on improving the mother-child relationship among preschool-aged children that would be cost-effective and disseminated easily,” she says.

The family coaches provide six in-home sessions that include coaching, video practice and positive reinforcement. They encourage an ABC approach, an acronym for Ask open questions, Build on responses and Communicate feelings. They then conduct follow-up assessments immediately after the program and again at six months and a year out. A new grant assesses the participants five and six years later.

“The whole goal of my intervention is to improve maternal support,” Valentino says. “We can even unpack maternal support into smaller components — what are the specific parenting skills that our intervention was able to improve or not.”

The results, published in the journal Developmental Psychology, have shown measurable benefits. Mothers who participated in the intervention improved in the explanation and sensitivity of their communication with their children. Children show improved emotion knowledge and memory, as well as better emotion regulation from baseline to six months later.

Valentino’s team is still collecting long-term data, funded by a grant from the Eunice K. Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.. Because the program is relatively brief, it could be easily replicated at a larger scale.

Anecdotal evidence is also strong. Rosita Rios and her daughter Gabriela, 9, participated three years ago. As a single mother of two kids, Rios says she used to get frustrated and yell at her kids to get them to understand. She says she learned so much in this program that she has taken several others since.

“I realized I need to sit down and talk to the kids,” Rios says. “I tell them they are leaders and they are going to go to college. My daughter before, she never expressed what she felt about anything. She’s still pretty shy but she’s grown a lot.”

Likewise, Kandzierski says Steven is thriving at St. Adalbert’s this year after struggling at a different school the previous year. She says she and her husband find themselves naturally asking their kids more questions, employing the skills taught by Rosemary, their family coach.

“The best thing about the program is Rosie,” Kandzierski says. “She’s really had an impact on Stevie.”

Kandzierski’s grandfather used to make painted goose eggs to give out to close friends. Steven insisted the family give Salinas one of these heirlooms as a Christmas present two years ago.

Salinas recently called to say she’d just gotten out her Christmas decorations and always thinks of Steven. The red and gold-trimmed egg nestles right in the center of her tree.

First published by the Office of Public Affairs and Communications

- Writer: Brendan O’Shaughnessy

- Photography: Barbara Johnston and Matt Cashore

- Creative: Taylor Packet and Olivia Rotolo

February 10, 2023

More Like This

Related PostsLet your curiosity roam! If you enjoyed the insights here, we think you might enjoy discovering the following publications.