The Competitor

For this girl, the prettiest chains were the ones hanging from the iron rims above the blacktop.

“Chain nets,” Muffet McGraw says. “Everhart Park.”

When you made your shot, it made a gentle jingle, the wind chimes of her childhood.

She’d play basketball with the boys. All the time. From when she was in grade school in West Chester, Pennsylvania, through high school.

“I don’t remember ever being afraid,” says McGraw, who was born in 1955. “I didn’t think anything of it really. Just that I wanted to get better. I’m going to get better playing against guys, so that’s what I’m going to do. . . . I’m always the person that was motivated when you said, ‘You can’t do that.’”

Back then, she says, it was, “You’re a girl. You can’t do that.”

McGraw was a feminist before she knew what it meant.

What followed was a lifetime of self-discovery as one, realizing that through basketball she could empower women — and herself.

To use a double-entendre as blatant as a double dribble, McGraw is a game changer. She’s already immortalized in the Basketball Hall of Fame, yet she’s still making history in real time. She’s the head coach of the defending national champions, coaching in her 32nd season in South Bend. Eight Final Fours. Two national titles. At this point, she’s an institution — in part by changing the institution for the better.

“I’m trying to empower women and get them to understand that honesty is important, confidence is important — that’s one of the things that women struggle with,” McGraw says during a visit to her campus office on an autumn afternoon. “So I’m trying to build that confidence in them . . . being the role model that is willing to fight for women and what we’re up against in so many areas.

“I’m mindful of the fact that women, and young girls especially, are looking up to my team, and to me, and how we handle ourselves. That’s why it’s so important that we are seen as strong women. And yet, people want to talk about my shoes, which is OK, but do you ask Mike Brey what shoes he’s wearing?”

Every summer, McGraw has her players and staff read a book. In 2017 it was Admiral William H. McRaven’s Make Your Bed: Little Things That Can Change Your Life . . . And Maybe The World. This year, it was a slim title by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, We Should All Be Feminists.

“She’s a Nigerian woman,” McGraw says, “and she talks about how women are looked at, especially over there, and how it’s still a man’s world — and what we gotta fight for. Really, all we want is opportunity. Equal opportunity, equal pay, you know, we want to be treated the same. It’s all we want.

‘I kind of look at my team and go, “You don’t know the struggle that my generation went through to allow you to be where you are now.”‘

“So I had the girls define feminism for what they thought it was. And then we just talked about — are you a feminist? I thought the best thing was that they all defined it in a really smart way. They’re smart kids. So they would explain it in their own words, and it basically comes down to equal opportunity.

“‘Well, are you a feminist?’ ‘I don’t know,’ some would say. And I’m like, ‘Wait a minute, you just defined it, aren’t you that?’ They’d say, ‘Well, yeah — thaaaat.’ But there’s a very negative connotation of what a feminist is, and they’re like, ‘I don’t hate men.’ I was like, ‘Well I married one! I don’t hate men either.’”

She wants her players to think critically about stereotypes.

So I ask her: “Are you a feminist?”

“I am,” she asserts.

“Have you always been?”

“Oh no,” she says. “I didn’t know that I was — until probably when I came here.”

She shares more than just a name with Ann O’Brien.

McGraw’s mother, who turned 94 this year, “was kind of a fighter,” Ann “Muffet” McGraw says. “She did the women’s stuff, but you can always tell that she wanted more. I learned a lot from just watching her.”

There were eight O’Brien kids, so it was almost like two basketball teams crammed into the house. The lessons of McGraw’s childhood were raw: Life isn’t always fair. You’ve got to scrap to get what you want. Nobody is a standout. And resilience is required.

“She never had anything easy,” McGraw says of her mother. “She was always working for more. My dad played basketball, but I don’t know, I think my mom might have been more competitive. . . . She had a mastectomy, she had cancer. My brother died when I was a sophomore in high school. So they got through that. And my dad died probably 10 years ago. She gave my brother a kidney transplant, but he ended up dying. So she suffered a lot. But she always came back, you know? That was the thing she kept thinking when something went wrong. You gotta get up, you gotta keep fighting.

“My dad worked. My mom, of course, stayed home because that’s what you did back then. He didn’t do a thing around the house. He was actually a big chauvinist. And it’s funny, because he did come to all my games, but he definitely had the [mindset of] ‘Women are supposed to do this and do that.’”

McGraw can still picture the priest who shared the big news when she was in seventh grade — there would be a new girls’ basketball team. They would play six-on-six. And wear bloomers. But it was basketball.

By high school, it was five-on-five. And in 1973, Muffet O’Brien headed to Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia, about 20 miles east of West Chester. Women’s basketball was a new varsity sport. No scholarships. No per diem. No provided practice outfits or sneakers. But it was basketball. The players themselves would drive team vans to road games. When she was a senior, the Hawks attended a national tournament, so the players got to stay at a hotel — four to a room.

“To look back on that and feel like we were pioneers that got it going — you know, you have to start somewhere,” she says. “What we put up with — we went through a lot to get where we are now. . . . I kind of look at my team and go, ‘You don’t know the struggle that my generation went through to allow you to be where you are now.’

“So now I feel like we still have a long way to go. Let’s not get satisfied.”

She married Matt McGraw in 1977. She surprised her soulmate at the reception — while going in for the garter, he saw the soles of basketball sneakers. Theirs is a love story. To the coach, he defines “teammate.” They lead the league in laughs. He goes to all the games.

“And he does everything at home,” she says. “He cooks, he does the laundry. He does it all.”

Two years after their wedding, Matt took a job in Alabama and Muffet briefly became a volunteer assistant coach for the women’s team at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. One day, she attended a meeting in Tuscaloosa of coaches from many schools and many sports.

“Looking back, I don’t even know why they let me go,” McGraw says. “But it was fun. Everyone was sort of, for want of a better word, bitching about what they didn’t have that they needed — and after a few minutes of this, Bear Bryant got up.”

She alters her voice to sound like the country-fried football coach who led the Alabama Crimson Tide to six national championships.

“He said, ‘I just got one thing to say. When you wiiiiiiin, you get what you want.’

“And so I was like, ‘That’s a good philosophy.’”

One of the first feminists in her basketball life was a man.

In 1978, after McGraw’s graduation, Jim Foster had taken over as the women’s basketball coach at Saint Joseph’s. After her stint in Alabama, McGraw played in the Women’s Professional Basketball League. Point guard. She played for the California Dreams, and it was a dream — she was actually being paid to play basketball, though it was $11,000 and the checks didn’t always cash. After one season, she returned to her alma mater in 1980, to work for Foster.

“He was my first mentor,” McGraw says. “He just had a great philosophy and a great way of looking at life. It was always about life lessons. Me, I was all basketball, which is kind of funny — he was the guy and he was all about life, and I was the woman, and I was all about winning and competitiveness.

“He would always give a really thoughtful response to a question. He would always think about it and mull over it. And he read a lot. I just thought he was very philosophical, even-keeled, just a great guy to bounce things off.”

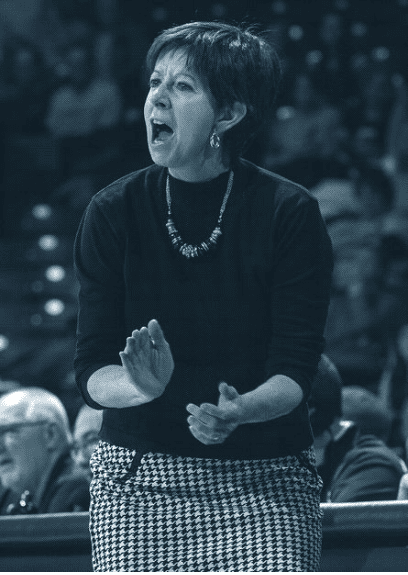

Photo by Michael Hickey / Getty Images

Photo by Michael Hickey / Getty Images

Two years later, McGraw took her first collegiate head coaching job, at Lehigh University, 50 miles up the road. She stayed there five years. Never had a losing season.

Then, on May 18, 1987, McGraw was introduced as the head coach of the women’s basketball team at Notre Dame.

“You know, I think we took a lot back then,” says McGraw, who speaks fast, often in short sentences laced with her quick wit. “We waited. Even when I came here, the men’s assistant coach said, ‘Here’s how it works: We practice when we want, for as long as we want, and then you guys can have the court.’ That was here. So you kinda go, ‘OK, well, that’s how it was when I was in college, that’s how it was when I was coaching at other places, so we’ll have to figure out how we’re doing that. But I’m not going to take that too long.’”

She hadn’t forgotten. When you win, you get what you want.

“So we took a little bit, and then gradually started to fight,” McGraw says. “We had some gender-equity discussions about where we were and how things should go. . . . I don’t think it was a particular straw that broke my back. I think at some point I just had enough. And that was it. And so we started talking about — how can the men do this and we don’t do that? Why are the men getting this, and we’re not? How come they’re traveling by plane and we’re taking a bus? This was in the ’90s.

“Pat Summitt, I think, is somebody that everybody looked up to for what she did for the women’s game,” McGraw says of the late, great University of Tennessee coach. “I just loved reading her comments, I read all her books. Anytime there’s an issue in women’s basketball, everybody would be like, ‘What did Pat think?’ To see her have that reverence and respect around the nation is something that I kind of aspire to. That’s what I want to be able to do, to help other women, to help our game. And initially, I never really got involved, and then watching her get on the board of the coaching associations, I got on the coaches associations. I was doing more for the coaches.”

The first time McGraw saw Niele Ivey play, “I’m pretty sure she was 0-for-13. And I loved her.”

There was just something about Ivey. Her competitiveness was contagious. The point guard played basketball like McGraw would, back when the nets were chains.

“I always felt a connection to her,” McGraw says. “But also, like — I wanted to look out for her.”

Ivey ’00 was a high school standout in St. Louis. Many summer mornings, the old sky-blue Honda Accord would pull up as the sky became blue, and Ivey’s best friend, LaTonya Jackson, would drive them to the Y to play. McGraw occasionally visited just to watch. This sure made an impression, the coach coming to her turf. Not just to her games, but to where she hung out and worked out.

When Ivey made her official visit to Notre Dame, she felt this strange, comforting feeling, as if she hadn’t left home. There was just something about Muffet McGraw. Her competitiveness was contagious. Ivey’s mother sensed it, too — that this woman would bring things out of her daughter.

Five years and two knee injuries later, Ivey returned to St. Louis. It was the site of the 2001 NCAA Women’s Final Four.

“Storybook,” McGraw says.

Ivey poured in 21 points — and swiped five steals — to beat Connecticut in the semifinals. And then, with family and friends in the crowd, Ivey tallied six steals in the title game, the 68-66 win against Purdue.

They’d won the first women’s basketball national championship in Notre Dame history.

Ivey was named to the All-Tournament Team, along with the indomitable Ruth Riley ’01, at center.

And the court where it happened? The hardwood became the flooring in the lobby of the Notre Dame women’s basketball office.

“She’s allowed me to blossom,” Ivey says, “just giving me the tools, outside of just being a point guard. She did really a great job of just molding me to be a young woman. . . . She instilled a lot of confidence in me. I felt like, I already had the morals and values that my mom instilled in me. But I felt like Coach McGraw did a great job of kind of continuing what my values were.”

These days McGraw’s star playmaker is back at Notre Dame. Soon after Ivey’s five-year WNBA career, McGraw gambled, giving her a first shot at an assistant coaching job in 2007. That’s rare, even for a former standout, to nab one of the three coveted assistant gigs at a top school without any coaching experience. But this was Muffet McGraw and Niele Ivey. It just made sense.

More than a decade later, it’s still working. Notre Dame won its second national title in 2018. Fans will remember them forever — junior guard Arike Ogunbowale’s buzzer-beaters to win both the semifinal over Connecticut and the national championship game against Mississippi State. But for McGraw, this team also made a historic impact for what it didn’t have.

“I have an all-female staff for the first time ever, one of the few in the country,” McGraw says. “I like that. I like having that and having people go, ‘Look, they got all women on their staff. You don’t need men to be successful.’ I always used to have a guy on my staff because all the recruits’ coaches were men. And there’s a guys’ network. I thought I needed that to get in. But now I’m so happy that my team and people can look up and say, ‘Look at these women. We can have a leader that’s a woman, that’s a wife, that’s a mother.’”

The 2017-18 season, McGraw admits, was the most rewarding of her career, because the Irish overcame overwhelming adversity — four key players suffered season-ending knee injuries. Four! And then to win both Final Four games like the end of Hoosiers?

She sure deserved a Corona Light.

That’s the coach’s favorite beer, and McGraw threw back a couple at the hotel, joined by family and friends, her staff and some former players. Even members of the old Lehigh teams were there. Toasts and cheers. Someone brought champagne. Matt McGraw was there, naturally, as was the McGraws’ son, Murphy.

And, of course, Niele Ivey, now a national champion as both a player and a coach.

It’s hard for nights to get better than that one was for Muffet McGraw.

In retrospect, it makes sense that it was Muffet McGraw, of all the coaches in the country, who allowed her players to make the headlines.

Before a 2014 game, they came onto the court wearing T-shirts that read “I CAN’T BREATHE.”

Placed in a chokehold, a man named Eric Garner had died while being arrested by police in New York. A grand jury decided not to indict the officer. Protests ensued nationally, notably from athletes. The Notre Dame players wanted to support the Garner family.

“It was kind of a big thing, because when athletes take a stand on something there is always a controversy,” McGraw says. “So what do you do as a woman, as a leader? Do you let your team voice their opinion and do that prominently? Or, do you say, ‘No, we’re not going to do that?’ So I was proud that they wanted to do that, and we weathered the storm and got through it.”

There were repercussions, some expected, some not. A social-media firestorm. Frustrated fans. McGraw had to have tough conversations with some officers who worked the games and felt the team was disrespecting police.

“With society, you know you’re going to get a lot of backlash,” Ivey says. “And it’s Notre Dame. So, a Catholic university. You have very conservative fans and tradition and alumni here. [The players] knew that they had [McGraw’s] ear. They had the confidence to sit her down and ask her, ‘You know, coach, we believe in this very strongly,’ and she was so proud of them, to be able to step up to present what was important to them. And then for her to back them and the staff to back them? I thought that was a pivotal moment in the history of Notre Dame, which I was so proud to be a part of. And that’s just another example of how she tries to help empower our girls.”

For McGraw, some of the most rewarding moments with her players come after they leave Notre Dame. She reconnects with them as adults — mothers, leaders, motivators. She beams when her WNBA players stand up for bigger salaries and players’ rights. McGraw allows herself to be satisfied with what’s been accomplished while staying hungry for continued progress.

The lesson? “Don’t wait to be asked,” she says in her office, which features a framed photo of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. holding the hand of Rev. Theodore Hesburgh, CSC, the former Notre Dame president, during a 1964 civil rights rally.

“Women, we’re hesitant to apply for jobs. We are not confident, we don’t have a network. Men are so good at that. And so confident. It’s like they are born with confidence. I think it goes back to dating. You know, we had to wait to get asked to the prom.

“I think in business, we’re still waiting for a guy to say, ‘Hey, I got a job for you,’ instead of saying, ‘I think I can do this.’ We’re very loyal, so we want to stay where we are. It’s very different.”

Gender roles, she says, are as antiquated as the set shot. She taught that to Murphy, who cooks for the family and, she explains, “is definitely a feminist.” She remembers him coming home one time from a sleepover. He couldn’t believe it: At that kid’s house, the mom did the cooking.

McGraw gets flustered when people call her team the “Lady Irish,” wondering why her team would need that label, but the “Gentleman Irish” don’t. She will squirm when someone compares her outfit to the opposing coach’s — she wants to dress nicely, sure, but it shouldn’t matter. And time and again, she is asked, alas, “Just how do you crouch in heels?”

“I think there’s a gap between the men and women,” she says. “I think there’s a double standard. . . . We have a lot of men coaching women in our game, and I think they’re treated a little differently. Players expect different things from a man than they do a woman. I think if I talked to them the same way that some of the male coaches do, I don’t think that would go over as well, because you just have a certain expectation for how a woman is going to treat you.

“I just do think that there’s still room to grow with Title IX in terms of the whole support staff and how you’re treated. I mean, we’re getting there. Our Final Fours are selling out, but we still got some work to do in the regionals.”

It’s interesting that McGraw is more of a feminist now than in the 1970s, when the movement rose to address inequalities in gender roles, the family and the workplace. But really, she was part of it all along, just by being herself, coaching and teaching and growing.

“At Notre Dame, I think it’s having more of a platform,” she says. “Realizing that people were looking at me — and me starting to think that I gotta do more. I just didn’t think I ever did enough for the women’s game. So I wanted to do more and be a voice that people would hear.”

When Jessica Shepard first got the voicemail, she listened to it again, just because it was so cool. She told her friend: “Muffet McGraw just called.”

The Nebraska native was transferring from the University of Nebraska.

“I talked to a bunch of other college coaches,” Shepard says, “but there’s something about this, you know? Muffet McGraw — it was something special. And then just getting to talk to her, you instantly just realized how special a person she is.”

In 2017-18, her first season at Notre Dame, Shepard became a national champion, averaging 19 points per game and 9.3 rebounds in the NCAA Tournament, while scoring the most points for the Irish (19) in the title game.

In a quiet moment this fall in the Purcell Pavilion, with gold-trimmed banners hanging above like chain nets, Shepard explains Coach McGraw this way: “She is going to challenge you as a person, and as a basketball player, to be better than you ever thought you could be.”

She recalls the first team gathering after reading We Should All Be Feminists and flashes a smile.

“It just gives you a different perspective on things,” she says. “I think a lot of us didn’t even know, you know, what feminism was — or had a different idea of what it really was. But just to sit there and have discussions with people who have been through some of it? And then us as younger adults to hear those perspectives? It really helps.”

We should all be Muffet McGraws.

Originally published in the Notre Dame Magazine by Benjamin Hochman, Winter 2018-19.

December 1, 2018