Savor the Inexplicable

Tragedy and joy collided in my life the week my father died unexpectedly and my wife —equally unexpectedly — discovered she was pregnant. My view of the universe changed, too, in a way I could never have predicted at the time.

Up to then, I didn’t give any thought to the existence of spirits. That was for fairy tales and New Age mystics. The world is already so fascinating in its verifiable reality that I wondered why people feel the urge to fabricate ghosts, fairies, sprites, specters, reincarnation and other figments of their overwrought imaginations.

That stiff skepticism was shattered a few days after Dad’s funeral, when I spotted him peering at me through the window of my front door, exactly as he looked through the window on Thanksgiving Day two months earlier. He had called that morning to say there was too much snow for him and Mom to make the trip to Minneapolis. But then he changed his mind and they showed up at our door with beaming grins, just in time for turkey.

A former coach, he was very fit and active for a man of 70 — I had recently chewed him out for climbing a ladder to paint the third story of his house. I never dreamed this was the last time he’d sit at our Thanksgiving table, or that the next year his first grandson would be there instead.

Stunned to see him, I shook my head, thinking, This can’t possibly be true. When I looked back, he was gone. At first I felt relief that I hadn’t slipped into the pages of a ghost story. Then I felt overwhelmingly sad. I wanted so much to tell him I was going to be a dad.

But he came back. I sensed him sitting at the kitchen table and passing on the staircase; I thought I heard him whistling in the basement and scoffing at “know-nothing” sports commentators on the radio. His spectral visits cheered me at a tumultuous time — my mother had a major stroke the day he died — though part of me vehemently resisted the idea that my dead father was lounging around the house.

One night about six weeks later, Dad came to me in a dream. He didn’t say anything but flashed his always reassuring smile as a song played in the background. I had heard it many times growing up but couldn’t remember the name. Jerking up from bed, I hustled downstairs and dug through my record collection for what I knew was his favorite LP, Benny Goodman’s Greatest Hits. I played a few seconds of each cut until finding it — an exquisitely melancholy instrumental titled “Goodbye,” which Dad once said Benny Goodman always played to close his shows. That was the last I heard from him.

But he paid us one more visit — at the birthing center of St. Mary’s Hospital. This time I didn’t notice his presence, but the midwife did. At the most grueling point of labor, she told my wife, Julie, that her father was in the room. Later, after holding my son for the first time, I asked the midwife what the unexpected visitor looked like. Tall, white hair, glasses, wearing a sweatshirt, she said. My father to a T.

There’s Got to Be An Explanation

As a journalist, I feel a duty to probe beneath the surface for the actual cause of baffling events. Objectively, I knew, there had to be some way to account for Dad’s appearances. In the shock of my loss, maybe I subconsciously conjured connections to him in my mind. And perhaps savvy midwives realize the value of comforting women in the throes of birth by saying that family members are beside them. When asked about it, they offer general descriptions that fit many if not most grandparents.

These explanations make a lot of sense when you consider that Dad never appeared to me again. Yet I can’t forget the day my two-year-old son calmly reported that Grandpa lived in his bedroom closet. I took this lightly until a few months later when we were visiting family friends and he pointed to a snapshot in their family photo album, announcing, “There’s Grandpa.”

“No, that’s Daniel’s grandfather,” explained Daniel’s mother. Glancing at the photo, I shook my head in disbelief. It showed a man who looked just like Dad.

There’s probably a rational answer for that, too. But I had to admit the accumulation of evidence that Paul Walljasper’s spirit lived on in some form could not be so easily dismissed. At some point, you have to trust your own experience as much as what you were taught about how the world is supposed to operate.

While my ingrained suspicion about the supernatural has not evaporated, it’s now tempered with a humility about the limits of human certainty. Even with our amazing tools of scientific inquiry and detection, not everything in the world can be readily explained. At least not yet. I am struck by a question posed by the controversial former Cambridge University biologist Rupert Sheldrake, who asks how people would have greeted the suggestion that human voices could be carried long distances through the air in the years before Heinrich Hertz discovered radio waves in 1886.

But I had to admit the accumulation of evidence that Paul Walljasper’s spirit lived on in some form could not be so easily dismissed. At some point, you have to trust your own experience as much as what you were taught about how the world is supposed to operate.

Learning how the world works is an act of evolution. No one is sure, for example, how migrating birds know when and where to fly, but each spring and fall the skies are filled with proof that they do. And sometimes what we think about the world turns out to be wrong, or incomplete. Findings from the frontiers of quantum physics about the nature of subatomic particles have challenged prevailing models of reality dating back to Sir Isaac Newton.

To act as if what we know now is all there is to know seems to me more outlandish than believing in spirits. Nonetheless, many otherwise open-minded people discount what doesn’t fit snugly into reigning scientific theories. There’s a sort of fundamentalism afoot about what’s too wacky or woo-woo to take seriously — the unaccountable effectiveness of some placebo treatments, for instance, or the stories of people who’ve survived near-death experiences.You risk titters for being a dupe — or at least enduring a condescending roll of the eyes — while bringing up topics beyond the boundaries of rational certitude. Until this essay, I have been careful in telling the story about my father. Generally, I wait until I know someone pretty well and then bring it up toward the end of an absorbing conversation, often after a few glasses of wine. They usually respond with some remarkable, inexplicable incident of their own. And I’ve discovered that practical-minded friends with science or engineering backgrounds are just as eager to share their experiences as are those more steeped in the arts, humanities or spirituality.

Trolls and Leprechauns and Gnomes, Oh My!

So, do I think otherworldly spirits flit and flutter around us all the time, visible only to a few folk who are — choose your favorite — either enlightened or deranged enough to notice?

Well, yes! I have incontrovertible evidence that wee creatures like trolls, gnomes and leprechauns actually exist. I’ve seen them many times hiding in the nooks and crannies of lawns when I am out walking. They’re usually dressed in bright colors, with complexions resembling plaster or plastic, and they are easy to spot in springtime at garden supply stores. They exist in people’s imaginations, if nowhere else, and prove humans’ eternal attraction to the supernatural.

For me, the world has felt more magical since encountering Dad’s presence around the house. The experience pushed opened a door to mysteries in the universe, which I had bolted shut sometime after learning Santa Claus was a myth. I’m convinced stuff happens that makes no sense by any analytical measures. You think of an old friend for the first time in weeks and — ping! — she sends a text message. Or consider the fact that many hospital emergency rooms add extra staff on full-moon nights.

I believe what we don’t understand can be just as valuable as 100-percent certified truths. Many of the most jubilant elements of life — the power of love, the awe of nature, the secret of creativity — remain elusive puzzles no one has figured out completely.

This belief has led me to embrace a wider sense of wonder about the world. Released from the urge to immediately unearth an explanation for any unexpected experience, I let myself plunge further into it — reveling in what’s exciting and meaningful, acknowledging what’s uncertain and scary. Personally, I feel more alive and alert to the minor miracles of everyday existence.

As a well-behaved child, I concocted a make-believe friend who got into all sorts of trouble. He lived underground in the vacant lot next door to our house, and I called him Goatie.

Nearly every day, I stroll over to a grassy knoll in a Minneapolis park to gaze out at a stretch of trees and gardens with Lake Harriet in the distance. It’s my spot for relaxation, reflection and refreshment. Just standing there eases my burdens and instills a sense of flourishing possibility. Time seems to dissolve and — if I am lucky — the nagging to-do’s rocketing around my brain are held at bay. I am strangely connected to the wind, clouds, flowers, trees, birds, dogs and people — including the homeless woman who occasionally sleeps in the bushes. Through the seasons I smell lilacs, watch fireflies, hear crickets, admire fall colors, note geese flying south, ski the snowy hillside and, starting the cycle over again, spot buds on the lilac branches.

Once in a while I sense something stirring in the treetops — shimmering, whispering, dancing. It’s fleeting, and I can never quite make out what’s happening.

Refracted sunlight and soft breezes coming off the surface of Lake Harriet?

A surge of negative ions in the air, thought to have mood-elevating properties?

A momentary, staggering recognition of nature’s sublime beauty?

A visit from the Holy Ghost?

Or, as it seems to me, sprites and nymphs and sylphs — divine spirits found in Greek myths, Shakespeare’s plays, Yeats’ poems and Slavic folktales, who are variously associated with trees, waters, meadows or the sky.

These spirits twinkling in the trees are probably figments of my overwrought imagination, no more real than Harry Potter or my neighbor’s garden gnomes. But I am always glad to feel them around.

Epilogue

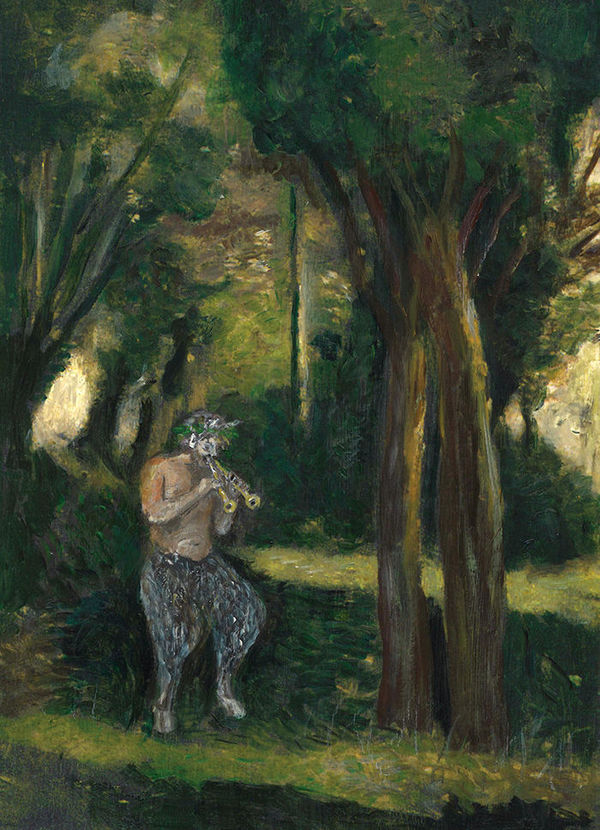

Intrigued by the appearance of magical creatures at my local park, I’ve been reading up on the gods, goddesses, demigods, heroes, monsters, spirits and other denizens of classical mythology. Recently a shaggy creature jumped out at me from an illustration on Wikipedia, offering fresh insight on events long ago.

As a well-behaved child, I concocted a make-believe friend who got into all sorts of trouble. He lived underground in the vacant lot next door to our house, and I called him Goatie. Unruly hair crowned his freckled face, with little horns poking out of the tangles. We enjoyed raucous adventures all over the neighborhood, and, when sensing my parents’ disapproval, I always blamed Goatie.

I now realize Goatie was a satyr, one of the half-man, half-goat figures who cavort with Dionysus, the Greek god of wine. Also known as fauns, they live a carefree existence dancing, playing the pipes and chasing nymphs around the forest.

I always understood Goatie wasn’t a real person. What I didn’t know is that he is very much alive in stories that have been told through the centuries. Indeed, a satyr named Grover Underwood is one of three main characters in the Percy Jackson & the Olympians novels and movies — a series approaching Harry Potter in popularity among kids.

How in the world did I tap into this deep mythological current when I was not much older than my son was when he said Grandpa lived in the closet? I seriously doubt my parents or anyone else in the small Iowa town where we lived introduced me to Greek myths at a tender age. The epic tales I heard as a child took place on the baseball diamond or basketball court, not in ancient Arcadian forests.

As always, one may offer a plausible explanation. Digging deeper I discovered that cartoon satyrs appeared for about 90 seconds in Walt Disney’s 1940 classic Fantasia as extras in a dance number. I never saw the movie until college, but clips might have played on Disney’s TV show when I was a preschooler. We didn’t own a TV until after I invented Goatie, but maybe I watched it at a friend’s house, forming an indelible impression in my young mind. However, I doubt it. Disney’s cherubic goat-boys bear scant resemblance to my scruffy, naughty friend.

No matter where Goatie came from, I marvel at the genius of the human imagination: Creatures appear out of somewhere just when we need them. Hanging out with a mythical satyr gave me permission to be more wild as a kid, just as encountering my father’s spirit consoled me at a sorrowful and challenging time in my life. While these things may not have actually happened, that doesn’t mean they aren’t true in an important way.

Savor the Inexplicable was first published in Notre Dame Magazine in Spring 2019. Jay Walljasper is the author of The Great Neighborhood Book and All That We Share: A Field Guide to the Commons.

March 5, 2019