Family Links and Finding the Sweet Spot

When the 40th U.S. Senior Open began with practice rounds on June 24, 2019, it marked the first time in its history the event was being played at a collegiate golf course. Yet as the players worked their way through the 70-par course, it became clear this was a venue unique not just for its location on a college campus. Second-place finisher David Toms remarked, “What struck me is how mature the golf course is for being a fairly new golf course. It looks like a historic golf course to me. I’ve always enjoyed playing historic venues and old-style golf courses.”

“Old-style,” maybe, but the impact of the U.S. Senior Open couldn’t be more here-and-now: An estimated 100,000 fans attended the event, along with more than 2,000 volunteers from 44 states and five countries. The economic impact on the area was estimated to be more than $20 million, and the week helped to bolster Notre Dame’s reputation for hosting world-class events, this time in a sport other than football.

The course, officially the William K. and Natalie O. Warren Golf Course, was opened in 1999 and is the result of the benefaction of William K. Warren Jr. ’56, a trustee emeritus who named the course after his parents and thus combined three of his enduring passions: his family, Notre Dame and golf.

But in a conversation with Mr. Warren and his son, John-Kelly, during the tournament, it became clear the golf course bearing his family name was about something else as well: giving back to the University he says “gave him more than he gave it” and set him up for success in business and in life.

The family is a key partner in the research mission of Notre Dame as well: Benefaction from the William K. Warren Foundation makes possible the Warren Family Research Center for Drug Discovery and Development, a state-of-the-art resource that helps spur interdisciplinary work to develop new treatments for a range of diseases.

How developing a top collegiate golf course revitalized its natural water hazards and fostered new research

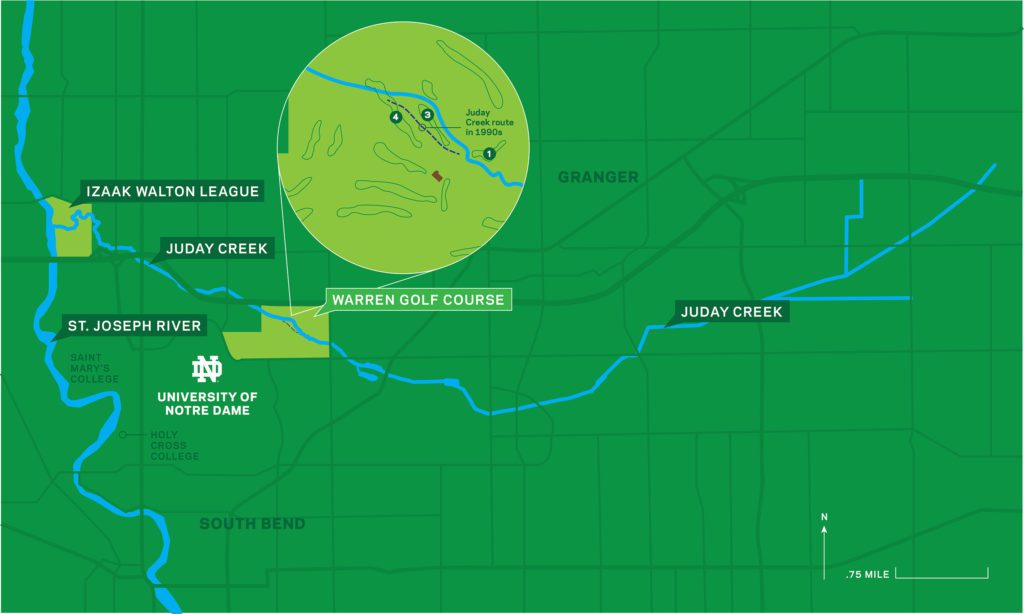

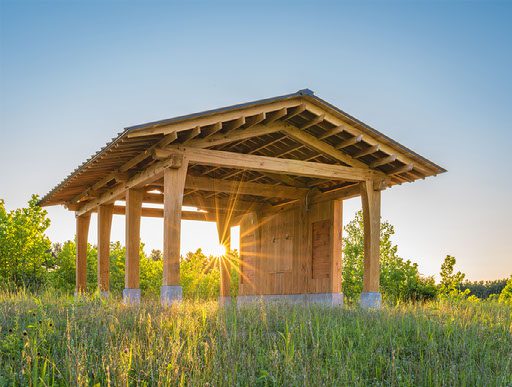

When competitors and fans arrived at the opening hole of the 2019 U.S. Senior Open, they were greeted by Juday Creek. Flowing through the University of Notre Dame’s Warren Golf Course, the stream is home to an important aquatic ecosystem that connects to the St. Joseph River and ultimately Lake Michigan. Although a golf course may seem like a surprising location for environmental research, the creation of this course led to the restoration of the degraded waterway – making it a valuable resource for hydrology and stream ecology research for Notre Dame students and faculty today.

Thanks to Notre Dame professors studying the stream, community watershed groups fighting to improve it, and federal regulations protecting waterways, Notre Dame embarked on an ambitious plan to restore this part of Juday Creek. This meant essentially rebuilding the stream around where the new golf course would be.

“When the restoration of the stream was announced, our researchers were given a unique opportunity to be involved in the construction, creating ideal channels and ecological settings to help Juday Creek’s ecosystem thrive,” said Gary Lamberti, professor of biological sciences and one of the lead researchers on the reconstruction. “We wanted to use this as a chance to develop a more natural flow for the creek and protect it from pollutants and fertilizers that are known to negatively impact the living organisms in the stream.”

After the restoration was completed in 1997, Notre Dame researchers continued to monitor Juday Creek’s ecological response. Through funding from the U.S. Geological Survey, Lamberti, along with researcher Ron Hellenthal, now professor emeritus of biology and director of the Museum of Biodiversity at Notre Dame, began monitoring habitat complexity, fine sediment accumulation, impact of the golf course, and the recovery of animal and plant life within the creek.

“Ron and I looked at different aspects – but all of our research was aimed at understanding how the restoration was supporting the ecological system of Juday Creek,” said Lamberti. “While I evaluated the stream habitat and recovery of the fish community, Ron monitored aquatic insects, pollutants, and overall water quality. We found that over a 20-year span, the creek’s new habitat promoted the resurgence of native fish and other organisms and partly reversed the prior adverse environment. While upstream development in the watershed still has negative impacts overall, the restored section of Juday Creek is something of an oasis for aquatic organisms.”

For decades now, Lamberti’s graduate students have also used the stream as part of their research, assessing everything from algae and fish to channel shape and water flow. But long before the restoration, faculty were using Juday Creek to teach Notre Dame students about ecology, potentially dating back as early as the 1860s.

Today, Lamberti and Jennifer Tank, Galla Professor of Biological Sciences and director of the Notre Dame Environmental Change Initiative (ND-ECI), continue this tradition by focusing the field component of their stream ecology class on the structure and function of Juday Creek. In these classes, undergraduate and graduate students study Juday Creek from its headwaters in the mixed farmland and suburban areas of Granger, Indiana, to where it meets the St. Joseph River at the protected Izaak Walton League property.

“Juday Creek presents a great opportunity for students to see the full scope of a stream since it begins in an agricultural setting, flows through an urbanized area before moving underground, and eventually flows to Warren Golf Course and to its confluence with the St. Joseph River,” said Tank. “Being able to study such a historically significant waterway in its diverse land use settings really highlights the impact humans can have on freshwater ecosystems and how collaborative engagement can restore systems if they become degraded.”From helping habitats thrive to tracing the transfer of disease in waterways, hydrology and stream ecology research spans a number of projects across the University and has real-world implications. Notre Dame’s state-of-the-art facilities enable researchers to collect quality data and engage in interdisciplinary collaborations across the colleges of engineering and science to tackle environmental challenges facing the planet today.

Read more here.

June 24, 2019