Charles Hubert Parry, The Fight for Right Movement, and the Women’s Suffrage Movement

View more in London in Song | "Jerusalem"

How exactly did the 4 stanzas from the Preface to Blake’s obscure poem “Milton” become one the best-known songs in England? The journey is quite extraordinary, and the story of the song is complex, but much of the credit must go to the poet Robert Bridges who in 1916 plucked Blake’s verse out of obscurity by including them in his collection “The Spirit of Man,” an anthology of poetry and philosophy that was assembled explicitly for patriotic purposes, to boost the moral of British soldiers and civilians during the Great War.

Robert Bridges was the poet laureate of the United Kingdom from 1913 to 1930 and was a literary scholar of considerable acumen. Why he thought the lines would be appropriate for inclusion in an anthology of patriotic poetry is unclear, and is indeed the least explicable part of the story of the song’s transmission, but it was an inspired choice. Like many of Blake’s poems, these lines can be read through various lenses with differing degrees of complexity. Stripped of the context of “Milton,” with its complex interweaving of biblical events, autobiography, and myth-making, Blake’s lines can be read as a celebration of the presence of the Anglican God in England and a call to arms to defeat external enemies.

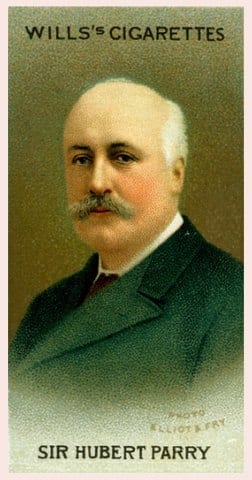

It was Bridges who suggested to Charles Hubert Parry that he set the words to music. Bridges approached Parry in 1916 to write a tune for the lines that “an audience could take up and join in.” Parry was a professor of composition and music history at the Royal College of Music, and is best known for his choral music. He is often understood as a rather stuffy example of the privileged musical traditions of late Victorian High Anglicanism (he was trained in the organ loft during his schooldays and educated through the degree systems of Britain’s ancient universities. He imbibed fully the aesthetics of high Anglican church music). He did, however, have a more radical side – he was a strong believer in the importance of folk music, and amateur music making in general, passing this enthusiasm down to his pupils who became some of the most influential folk-song hunters of the late Victorian period, including Ralph Vaughan Williams who attempted to infuse classical music with the indigenous tunes of Britain. It is probably in this context that Parry’s setting of Blake’s lines should be understood. His tune was explicitly intended to appeal to a popular audience, something that might inspire loyalty and inspiration, something that might be taken up as an anthem at large gatherings.

The song was given its inaugural performance in March 1916 at a rally meeting of the Fight for Right movement. It subsequently became the anthem of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Society, to whom Parry signed over the copyright. These two early uses of the song are instructive for thinking about the politics of the use of Blake’s words. The first performance exposes the song as unequivocally a piece of loyalist propaganda – the Fight For Right movement was designed to build support for British troops and to stave off flagging morale during the First World War. The second performance, the campaign for women’s right to vote, might initially strike us as much more progressive, so it’s instructive to remember that these two political movements had many members in common. This notably includes Millicent Fawcett, reminding us the history of politics rarely maps neatly onto our contemporary associations of “the left” and “the right,” a binary distinction that is rarely as rigid as its oppositional terminology implies.

So while the Blake scholar might wonder how the preface to “Milton” could end up being performed at Royal Weddings, the answer is quite clear: Parry’s setting strips the words of some of their complexity, doubling down on Bridges’ propagandistic inclusion of it in “The Spirit of Man.” Parry’s is a powerful, unambiguously patriotic tune, with rousing opening chords that are self-consciously anthemic, intended for performance by crowds in ways that express a collective passion for England’s “Green and Pleasant Land.”

2 minutes