Who Do We Say We Are? Irish Art 1922 | 2022

The Raclin Murphy Museum of Art renews its partnership with the University of Notre Dame’s Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies and the O’Brien Collection in Chicago to present Who Do We Say We Are? Irish Art 1922 | 2022. The exhibition exploring Irish national identity will be on display February 5 through May 15, 2022.

The collaboration is part of a multi-faceted, international effort to commemorate the historic events of 1922 and examine their legacy on contemporary Ireland. In spearheading these centenary events, the Irish government’s Department of Foreign Affairs brought its Midwest partners together with their peers from Trinity College Dublin, the Centre Culturel Irlandais and the University of Paris-Sorbonne to offer an unparalleled menu of music, literature, theatrical performances and visual arts.

The year 1922 marked a turning point for Ireland: the modern Irish state was essentially founded with the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty; James Joyce’s novel Ulysses was published; and the Irish Race Congress, a conference with an accompanying art exhibition that aimed to redefine Irish identity for an international audience, took place in Paris.

One hundred years later, Who Do We Say We Are? Irish Art 1922 | 2022 explores the connection between some Irish artists working today and their counterparts presented in the Exposition d’Art Irlandais, the exhibition of Irish art held in Paris in 1922.

“A focus of the exhibition is to investigate how artists, then and now, pictured Ireland’s history and geography, how their work informs our understanding of Ireland and its people, and what questions their work raises about the use of art as a tool of nation-building,” said Curator Cheryl Snay.

Paintings from the O’Brien Collection by Seán Keating, Jack B. Yeats, and Paul Henry—artists who participated in the 1922 exhibition—are juxtaposed with works by contemporary artists Patrick Graham, Hughie O’Donoghue, and Diana Copperwhite, among others, to explore issues of national identity rooted in the diaspora and landscape. An “In Dialogue” presentation of the Raclin Murphy Museum’s recent acquisition of Walter Osborne’s painting At the Breakfast Table (1894) rounds out the discussion of home and homecoming. And, expanding into the realm of photography, a selection of Ireland’s rural landscapes by Amelia Stein, RHA, engages epic legends and folkloric memories to reveal history and an evolving culture.

Created shortly after leaving Achill in 1919, [Paul Henry’s] Reflections across the Bog was painted somewhere in the West of Ireland, a region that Henry became most famous—even synonymous—for illustrating in his work. It is widely felt amongst art commentators that the image(s) of the West of Ireland that many can conjure in their imagination today—indeed during any time in the last one hundred year — often involves a visual memory of an encounter with a Paul Henry painting or print. Several of his paintings were used by the railway lines and by the Irish government as posters to encourage travel and so his widely distributed images and style became familiar to many both within and outside of Ireland. There is something very Henry-esque about Reflections across the Bog: the scale, and activity of the sky pressing down on the landscape which in this case, shows evidence of human activity (stacks of turf) but without being inhabited—a picturesque but lonely landscape.

Though it seems counterintuitive to imagine this, paintings in the canon of Irish art rarely depict rain or scenes where it is actively raining: as such this is a noteworthy exception. Sheets of mist and gently blowing rain emanate from the clouds, crisscrossing in a pattern for the viewer, which conjures an almost visceral awareness of the near ever presence of moisture in the Irish sky.

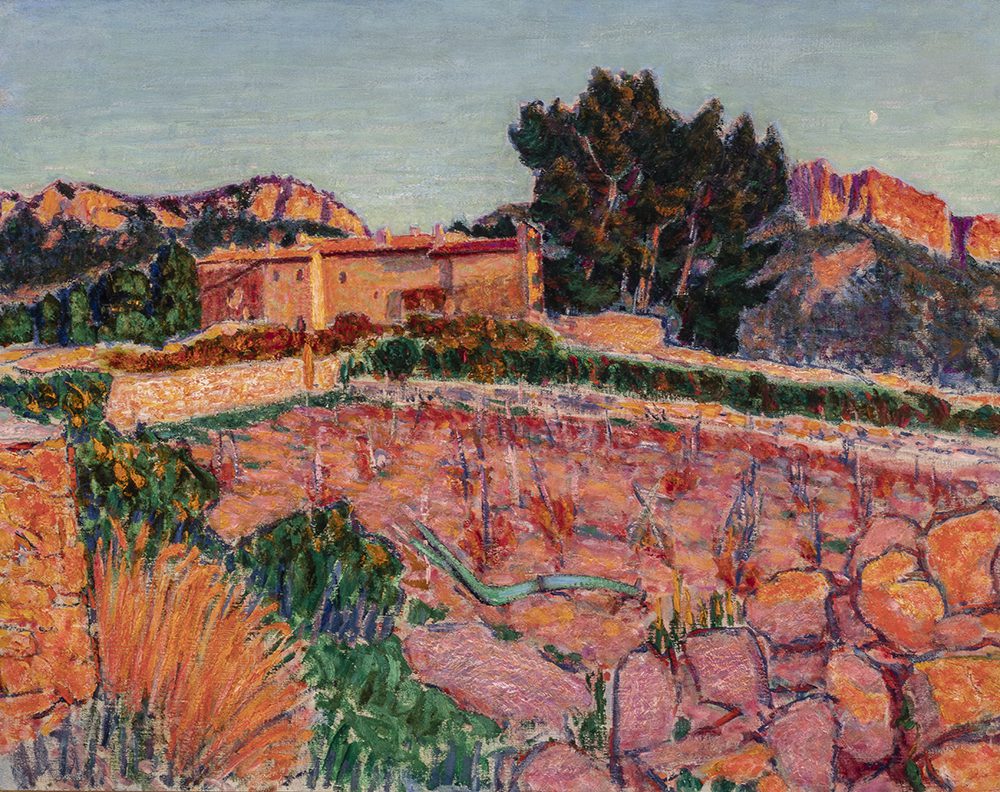

Roderic O’Conor is widely regarded as Ireland’s first “Modernist” painter given his early exposure to and adoption of the avant-garde Impressionist and Post Impressionist influences which, starting in 1883, he encountered in Belgium and France. His work is without equal amongst his fellow Irish artists, either during or, indeed, after his life. The distinctive sun-drenched warm light of [the southern French Mediterranean coastal town of Cassis] resulted in a burst of creativity for O’Conor and The Farm (Provence) is part of the body of work he produced and exhibited at this stage in his career. The villa pictured was his rented home while in the region and it is painted against the dramatic backdrop of the mountainous region of the Montagne de la Canaille. The light in this region heightened one’s awareness of color and this painting is evidence of that, bursting as it is with lush, warm contrasting tones. One can almost feel the warmth that this painting exudes—even the lonely, unattended plow in the middle of the field is rendered in bright green—an unlikely actual color for the plow but, thanks to O’Conor, it too is enjoying its moment in the sun.

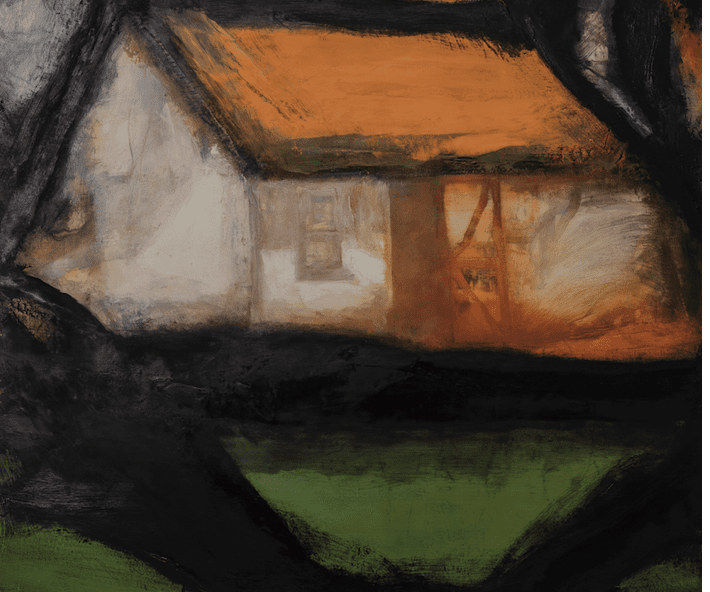

As pointed out by curator, Cheryl Snay, about this piece, Revolution Cottage is an expression of the artist’s concern with “ideas of place and identity in relation to historical and personal meaning that connect him with his heritage.” O’Donoghue has commented that discovering meaning and reflecting that with imagery in his art are often akin to an archeological dig, where rather than being a process of addition of line and color to a canvas, the image is a result of an emotional and artistic “excavation” and editing process which eventually enables the imagery to emerge. That artful editing is on splendid display in Revolution Cottage, which juxtaposes both the typical pastoral countryside setting of Pearse’s cottage with a modernist evocation of the Irish tri-color flag, itself suggestive of the life and world-changing patriotism that blossomed and matured inside of him while there.

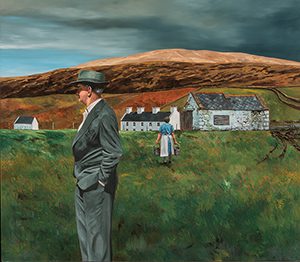

If one of the purposes of art is to provoke—thoughts, questions, feelings—then Women’s Work succeeds at first glance. The composition immediately begs the question, “What is happening here?” Painted in a style that is very realistic and being both a landscape and a portrait painting, it compels us to inquire into the uncertainty that seems to ripple both above and beneath the surface at the level of the paintings’ meaning. Is there a specific narrative at work? Are there multiple narratives at work? It is, perhaps, key to the power of the piece that my answer, your answer and the next person’s answer, might all be different, but each will carry its own personal and emotional weight and we will all remember the piece because of the connections those questions provoked for us.

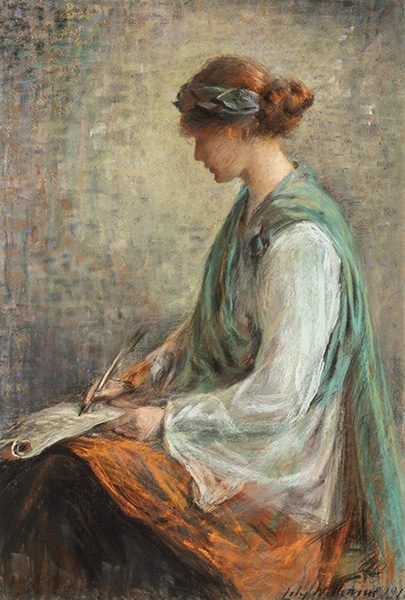

This evocative portrait of Hibernia by Lily Williams was painted at time of war in Ireland. In 1916 at

Easter, a Rising had taken place in Dublin and in other locations. It was quickly suppressed and the leaders those who described themselves as the Provisional Government of Irish Republic were executed. At this moment the artist, who had been closely associated with those involved, chose this subject matter. Hibernia, (the Roman name for Ireland) is depicted as a young woman with red hair gracefully held in place by a band suggestive of leaves, writing with a quill on paper or parchment. A romantic timeless study, yet a hundred years ago it was a bold statement of self-determination, indeed its creation has been described by curator of The O’Brien Collection, Marty Fahey, as an “outright act of sedition.” He has suggested that the subject could be composing a Proclamation or the constitution to come. The figure is draped here in the tri-color, which was not Ireland’s flag in 1916 as the country was still part of the British Empire. This flag had flown from the roof of the Royal College of Surgeons when it had been occupied by Oglaigh na hÉireann during Easter Week, when Constance de Markievicz, also an artist, was second in-command. The sitter is unknown, the provenance of the painting a mystery.

As Irish painter James Hanley said of Farewell to Ireland, “It is difficult to overstate the positive impact of JFK’s official visit to Ireland in 1963. He was one of our own….Although Patrick Hennessy used a stock press photograph he judiciously cropped the image, making for a more impactful composition. He placed the President firmly to one side removing any distracting background detail. He straightened and slightly elongated his back, as JFK’s posture was at times compromised by chronic pain, thereby making him appear stronger and more imposing. Finally, he edited the outstretched arms and hands into a more clear arrangement in the lower third of the painting. The more vertical dimensions of Hennessy’s canvas and his clever fine tuning of the composition of the original photograph made the image more immediate and underscored the adulation the President was held in on every part of his visit. This final moment at Shannon, our gateway to the States, shows an almost deified persona ascending Mount Olympus rather than the stairs to Air Force One.”

“On behalf of the entire Museum, we are deeply honored to be working in friendship and partnership with the O’Brien Collection, the Consulate General of Ireland, and the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies at the University of Notre Dame,” said Joseph Antenucci Becherer, director of the Raclin Murphy Museum. “These collaborations bring to life the rich and complex nature of culture in all its variety for our audiences,” he continued.

A Musical Interlude

A live performance of a rich, musical interpretation of the works on view in the Raclin Murphy Museum’s newest exploration of Ireland, Who Do We Say We Are? Irish Art 1922 | 2022 was held on April 29, 2022 at the Raclin Murphy Museum of Art.

New music commissioned and recorded especially for this exhibition focuses on the synergies between art, music and poetry. Co-producers Marty Fahey, curator of the O’Brien Collection, and Liz Carroll, composer and All-Ireland Fiddle Champion, interpret themes of national identity and the diaspora represented by the art on view in the galleries. (For more on the synergies between the arts, including pairings of pieces from the O’Brien collection with musical pieces and excerpts from Irish literature, visit “Irish Art . . . Amplified.”)

With paintings by iconic Modern and Contemporary artists exploring Irish themes of nation-building and identity from the O’Brien Collection in Chicago and a special focus exhibition of photographs by the internationally recognized artist Amelia Stein, RHA, the exhibition and album are part of the larger project States of Modernity: Forging Ireland in Paris 1922 | 2022.

Jointly sponsored by the Raclin Murphy Museum, the Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish Studies, the O’Brien Collection, and Ireland’s Department of Foreign Affairs, the concert will feature the Seamus Egan Project along with other musical guests playing selections from the album created for the exhibition.

Musicians and composers contributing to this project are Liz Carroll and Marty Fahey; Seamus Egan, Owen Marshall, Jenna Moynihan, and Kyle Sanna of the Seamus Egan Project; Mick O’Brien, Aoife Ní Bhriain, and Emer Mayock of the Goodman Trio; and Màiri Chaimbeul, Damien Connolly, Colman Connolly, and Liz Knowles.

The Catalog

The exhibition is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalog published by the O’Brien Collection with contributions by Billy Shorthall of Trinity College Dublin, Roísín Kennedy of University College Dublin, Aileen Dillane of the University of Limerick, and David Acton of the Raclin Murphy Museum. New recordings of Irish music inspired by the art complement the exhibition. The virtual recreation of the 1922 Exposition d’Art Irlandais that will be available online through Trinity College Dublin is a notable contribution to Irish studies and a welcome resource for scholars and enthusiasts alike.

This exhibition is made possible through the support of the Kathleen and Richard Champlin Endowment for Traveling Exhibitions, the Milly and Fritz Kaeser Endowment for Photography, and the Irish Government through the Department of Foreign Affairs and the Decade of Centenaries programme. Special gratitude is extended to The O’Brien Collection, lenders to the Exhibition and The Keough-Naughton Institute for Irish studies, Exhibition and Programming Partners.

March 11, 2022