Translation…or a hundred years of ulyssitude

On 02.02.2022 Joyce’s Ulysses will turn a hundred and its author a hundred and forty. Less than a decade ago, on 02.02.2012, my previous Italian translation of Joyce’s “book of the day” came out, and it is somehow strange, or rather uncanny, to go back to it now, in this time of solitude and confinement, to produce another edition of it, another centenary edition.

Ulysses is a book of the people, written for the people, and it is therefore a communal space of dialogue. Its many voices defy silences of all kinds.

When I worked on my translation in 2012, I was always surrounded by so many noises. Indoors there was a little baby crying or laughing intermittently 24 hours a day, and we also had a cat playing or meowing all the time—like Bloom’s cat at the beginning of the second part of Joyce’s great book.

Outside my apartment at that time, in the lively neighborhood of Trastevere in Rome, right in front of our door there was an Irish pub called Molly Malone—always full of clients drinking their days away in jolliness, sometimes among shouts and, not too rarely, amid profanities and bawdy jokes.

Joyce never liked to work in solitude and silence, and neither should his translators, I think.

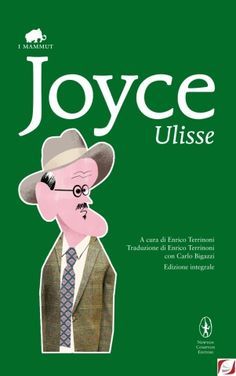

When I was asked to do a new translation of Ulysses, I accepted for the sole reason that the publisher wanted to include the original as parallel text. I immediately liked the idea, as I always thought that foreign editions of great books should incorporate the original too. This is not to diminish translation, of course, which is always a great thing for a foreign culture and for a book and an author; but translations of masterpieces should also be invitations to dive into that very magmatic linguistic space that deserves to be reproduced in a different language/culture in the first place, due to its borderless immensity.

As I work on this new translation of Ulysses now, here in Rome, there are no noises outside my window.

In normal times, far from being a cruel month, April in Rome is perhaps the liveliest time of the year. Spring breaks into our lives, class discussions continue in open-air bars, families meet up in the weekend to eat out in the countryside, and friends go out to watch matches together.

All is different this year.

I don’t meet students in person, and when I catch a glimpse of them on the screen, it’s always the sad, hopeful eyes of young ones deprived of their Spring that I see.

With my family, I live only three blocks away from my parents, from my daughter’s grandparents, and we haven’t been able to see them in the past six weeks.

In March, just before St Patrick’s Day, we would have had the first leg of the Global Ulysses conference at the Notre Dame center in Rome. Colleagues from all around the globe would have met here to discuss Ulysses ahead of the book’s centenary. Actors, musicians and writers would have mingled with young and established academics. A great friend of this venture and a friend of translations too, Jhumpa Lahiri, would have joined us, as Rome is her second home. All is on hold. All is put off. But our day will come.

Rome is strangely silent now. Living without outdoor noises for the time being is making me reflect on translation as an exercise in foreignness and confinement. The adjectives I can think of to describe this situation are: strange, extraneous, estranging.

Translation is an attempt at extracting, and translators are all Estragons, who, without their Vladimirs, are always inclined to dig out something from a text into whose cavities they were supposed to excavate productive tunnels. What they dig out is the very new material which will shape their new versions of those old books, for a translation is always a new version of an old text. It reveals new cavities, and in revealing them, it also re-veils them. Revelation, re-veiling: perchance revolution. Or rather, re-evolution?

Evolution is a continuous process, and it can also be argued that translation is the evolution of an old text. We naturally resist this notion, perhaps because we are afraid of the possibility that to resist might mean to re-exist. Resistance as re-existence is a stance that probably captures the very essence of translation: a text which, born out of a pretext, becomes the pretext for a post-text.

Hence its hybridity, its sense of foreignness which nothing will ever quench. A translation is born in and out of otherness, it lives in strangeness, it stays external, if not eternal, though sharing many a border with its inspiring text. A translator is always aware of the precious silence he is called upon to fill. To fill this silence with new sounds and noises is his job, in a never-ending infinite exchange, an endless negotiation which will speak to others “in silence,” as Cymbeline would say.

To translate means to silently understand that we are the others, we are the other person, the third person in the trinity of textuality, I mean: we are the post-text. The reason why we communicate at all is because we secretly long to be the others we are not yet: we silently crave to be the other who is unknown to us. We, in fact, are sometimes afraid of what we are not, Hamlet explained, and this is why we need to “fly to others we do not know of,” he admonished. But, if we are the others we do not know of, it follows that the enemy in us is not an enemy at all.

Translation means to accept and integrate. It means replacing silences with sounds. It is, Joyce would add, a “nightmaze,” an attempt to state that nobody owns words, nobody is the proprietor even of his own words, as those very words, once uttered, once they end up fulfilling their mission and become “actualized,” are no more ours.

“We are our own,” a character in one of Joyce’s best short stories says, and in Ulysses we read the echo of a long-gone poem in the expression “nobody owns.” How can we possess words without casting upon them a malevolent spell? Here’s the rub: the nightmare we translators face—and when I say “translators” I mean all of us, for it is impossible not to “translate ourselves”—is a horse we ride at night, carrying words, phrases, sounds, travelling in the dark. “Ride on,” voices from the silence say. “I could never go with you no matter how I wanted to.”

In the attempt to make a foreign text “our own,” we happen to lose it, for we loosen our brakes. We deliver not what was, but what will be. This is why we are all translators. Because we act upon ourselves, we play a role, a role written by somebody else. We identify with what we are not, in order to be once and for all what we finally want to be.

Translation is just a medium. It is a mirror, cracked if you like, reflecting not the past, fabled by the daughters of the immemorial, but the future which can’t be remembered unless one imagines it. By doing so, we relocate a text in some future space-time so that it can achieve some new life. Translation is an aim, it is always in progress; and the aim, its end, is to say that the game is not over yet. It prompts us to escape “the prison-house of language,” for a prison is always a maze, and from this labyrinth we can still flee. Linguistically, culturally.|

Translators will always be foreigners. They will not belong. They are their own. But, their words are our words. Their voices are the voices we once knew well. And if we knew them well in the past it is because, at the end of our day, the past is our only future.

__________________________

Enrico Terrinoni was a Visiting Fellow in Irish Studies at the Keough-Naughton Institute in Fall 2019 and a convenor of the Institute’s 2019-2020 Global Ulysses initiative, of which the Center for Italian Studies is a sponsor.

During his recent semester at the Institute, Professor Terrinoni taught a graduate seminar on Ulysses with Declan Kiberd, the Donald and Marilyn Keough Professor of Irish Studies and Professor of English and Irish Language and Literature. He also led a memorable roundtable on issues of translatability and reading as a modality of “infinite translation” at the Hesburgh Libraries—an event jointly sponsored by the Institute, the Center for Italian Studies, and Rare Books and Special Collections.

Professor Terrinoni is Full Professor Chair of English Literature at Università Per Stranieri di Perugia. His 2012 Italian translation of Ulysses won the “City of Naples Award” for Italian language and Culture. His Italian translation of Finnegans Wake, done in collaboration with Fabio Pedone, won the Annibal Caro Prize in 2017, and he was awarded the” City of Florence / Von Rezzori Prize” for translation in 2019.

Originally published by Enrico Terrinoni at irishstudies.nd.edu on April 14, 2020.

April 14, 2020