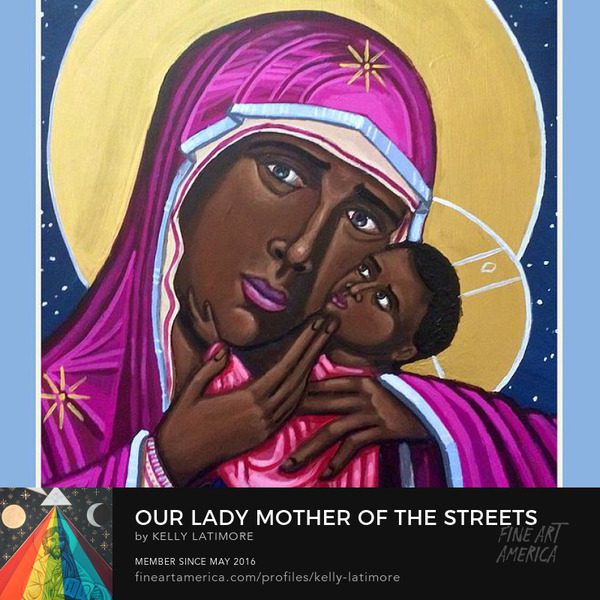

The third virtual event in the Medieval Institute’s Pilgrimage for Healing and Liberation series explored the sacred art of iconography and its intersection with racial justice. This event was moderated by professor Richard Klee, Affiliate Faculty member of the Notre Dame Initiative on Race and Resilience. Klee spoke with artist and iconographer Kelly Latimore from Saint Louis, MO. Latimore’s icons often mix classic orthodox iconographic imagery with figures representing the marginalized and the oppressed among us here and now. Latimore’s icon “Refugees: La Sagrada Familia,” in which the flight to Egypt is interpreted as Latinx immigrants crossing the desert, adorns the cover of Pope Francis’s book, A Stranger and You Welcomed Me. Latimore has also created a diverse array of icons of unexpected saints such as poet Mary Oliver, congressman John Lewis, and Mr. Rogers. To begin, Klee and Latimore discussed Latimore’s journey as an artist and important themes in his work. Their conversation was followed by an opportunity for questions from viewers.

Latimore studied religion and art at Greenville University. He started painting icons in 2010 while a member of the Common Friars, a small monastic farming community in Athens, Ohio. The community runs Good Earth Farm, which grows produce for local food pantries. That experience took his “spirituality from transcendence to communion, engagement, and embodiment” and taught him “that the way we use things is of the utmost spiritual significance” (6:06). Latimore became curious about icons, which are “written images” that point toward the person of Christ or the saints. He began tracing the lines of the old masters, like the medieval Italian painter Cimabue, teacher of Giotto. These artists of the past have “done the work of holy pondering” and continue to inspire Latimore (12:48).

Klee noted the influence of medieval perspectives on the body in Latimore’s icons of Saint Francis of Assisi. Francis entered into the suffering of the poor and oppressed and his life made “the invisible” presence of God “visible” in the world outside church walls. Latimore’s art is also influenced by the witness of Dorothy Day, co-founder of the Catholic Worker movement. Day’s life and example show that the work of caring for your neighbor is work that we can all do. As Day saw the face of Christ in the urban poor, Latimore makes icons that identify Christ with immigrants, refugees, and the homeless poor living in tent cities.

Latimore is currently working with parishes that want new representations of Christ as Black and Brown. In America, the dominant image of Jesus is of a blonde and blue-eyed white man. If church art only shows God and authority as white, then how do people of color see themselves in Christ, and how do people who are white see people of color? (36:31) Some of Latimore’s Black/Brown icons have provoked resistance. He made the icon “Mama,” an image of the Pièta representing George Floyd and his mother, not only to mourn Floyd’s death, but also to ask viewers: What are we going to do so that mothers are not continually losing their daughters and their sons, who are unjustly murdered by the State, just as Mary did 2,000 years ago. (26:49) The pushback that icons like this one receive can be productive when it generates dialogue around racism and xenophobia. Sacred art can help us name the racism within ourselves and name the ways we are not loving our neighbor well. (30:03)

Latimore believes these hard conversations need to happen if we’re really going to be a church that is welcoming of everyone. “To deny the image of God in anyone is a complete denial of the Incarnation.” (37:54) Moving forward, he hopes to foster dialogue around representation and inclusion within the church.

Visit the event page for more.