Faith and Fatherland: Belief and the Irish Catholic Experience

On Friday, September 9, 2022, a standing-room-only crowd gathered in Jenkins–Nanovic Halls to hear Enda Delaney, professor of modern history at the University of Edinburgh, deliver the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism annual Hibernian Lecture. After a greeting and an introduction by Kathleen Sprows Cummings, Delaney thanked the Ancient Order of Hibernians and the Ladies Ancient Order of Hibernians for sponsoring the lecture and then described his topic, “Faith and Fatherland: Belief and the Irish Catholic Experience.” How important has belief been to the Irish Catholic experience, not only on the island itself but also for those who settled abroad?

Over the decades, the subject has drawn interest from a range of distinguished historians, including the late Monsignor Patrick J. Corish, former Cushwa Center director Jay P. Dolan, Cara Delay (College of Charleston), Sarah Roddy (Maynooth University), and Colin Barr, professor of modern Irish history in Notre Dame’s Keough School and the director of the Clingen Family Center for the Study of Modern Ireland. Yet elucidating the theme requires great effort, Delaney insisted, due to sourcing obstacles: the predominantly oral nature of historic Irish culture has left behind a dearth of documentation, an impediment for interested scholars.

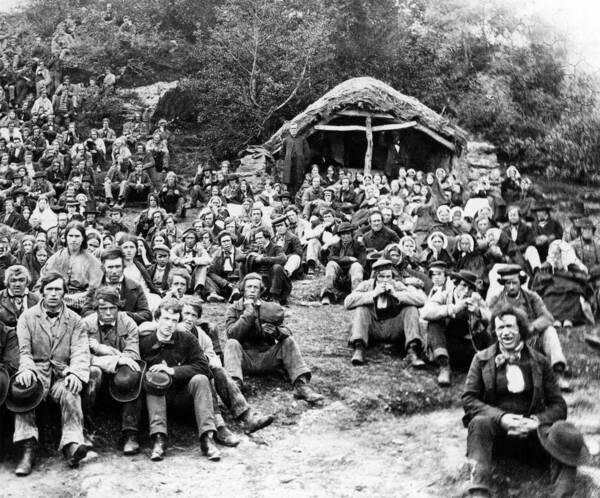

Those sources that do exist each have their own shortcomings. For example, though many travel writers depicted Irish religion, they were not only transient onlookers but also frequent propagators of what Delaney labeled “misery tourism.” Primarily, their accounts were intended to sell copies, not to inform future historians. Drawing any firm conclusions from records of attendance at religious rites is also fraught since penal codes, a shortage of priests, and distance from churches all worked against regular participation. Published catechisms have presented another possible fount of data, but even their usefulness must be qualified; a semi-literate society would have imbibed much more from spoken sermons than from written compilations of Church teachings.

Next, Delaney explained how scrutinizing these varying modes of transmission can clarify change over time in Irish Catholic belief and practice, namely from a more communal faith to a more dogmatic religion. For centuries, Irish Catholicism comprised a mixture of Church-sanctioned doctrine and unofficial folk practices, with the latter passed down not just by local priests but also by family and friend networks within a community. One popular interpretation of Irish history has viewed the 1840s and 1850s as a hinge point for a “devotional revolution,” as the disruption of that period undermined other sources of joint identity—especially the Irish language—leaving the rites of Catholicism as one of the few remaining points of solidarity. From that instability, reformers such as then-Archbishop Paul Cullen would construct a faith that was “disciplined, universal, and orthodox.” Delaney also mentioned the dissenting view of scholar David Noel Doyle, who challenged the notion of a clean rupture and instead posited multiple Irish Catholicisms, distinguishable by region. In this telling, Irish Catholics in Connaught and Ulster retained more of the traits of their forebears, inheriting their faith via communal dissemination. Catholics in Leinster and Munster absorbed the Cullen-directed, Anglicized faith via formal indoctrination, with this latter version eventually becoming dominant throughout the island.

What of Irish Catholicism beyond Ireland’s shores? Delaney disputed the clumsy trope that emigrants jettisoned their faith immediately upon leaving home. In part, that narrative emerged from the Church itself, as priests emphasized the numerous threats and temptations emigrants would encounter in the wider world. Rather, Irish Catholicism took different forms and played different roles in global contexts. Delaney thus cited Dolan’s work on Irish Catholics in the United States, where the urban parish transitioned from “a religious institution . . . to a community institution,” with Irish priests serving as local “mediators” between newly arrived Irish Catholics and their host cultures. And even after their departure, emigrants still exerted influence on Catholicism within Ireland. Many new churches, for example, were built using funds sent from Irish expatriates, ultimately displacing a well-established “outdoor religious culture” exemplified by open-air Masses.

The engaged crowd made eager use of the Q&A time to solicit Delaney’s input on a range of topics. Tom Kselman (Notre Dame, emeritus) sought additional clarification on the shift from communal to dogmatic religion, asking whether the quality of belief changed once Irish society underwent the transition. Rory Rapple (Notre Dame, history) wondered how variations in language have governed subsequent evaluations of Irish religiosity. Delaney agreed with Rapple that religious sophistication could become diluted in the process of translating from Irish into English and due to deficiencies in the interpreters rather than the imaginative capacities of the subjects.

Gráinne McEvoy (Notre Dame, Nanovic Institute) asked how emigration altered Irish religious practice, citing as one prominent example the “American wake”—the symbolic death ritual that Irish communities performed for emigrants departing for North America, when poverty and the rigors of travel meant that migration often represented a final parting. Delaney noted that the American wake likely receded in significance once the economic prospects of the emigrants improved, making occasional transatlantic visits less cost-prohibitive. Julie Morrissy (NEH Fellow, Keough-Naughton Institute) related some of the rituals Delaney had described to the religious innovations that arose during the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, when social distancing restrictions required radical departures from long-held funeral traditions. Several other guests weighed in with questions about the place of faith during the Great Famine and how religious and cultural identities had interacted in the process of assimilation in the United States, before Cummings closed the event with thanks both to the audience and to Delaney.

This recap was originally published by the Cushwa Center for the Study of American Catholicism in the article “In review: Fall 2022 at the Cushwa Center” and was written by Philip Byers, a postdoctoral research associate at the University of Notre Dame’s Cushwa Center.

September 9, 2022