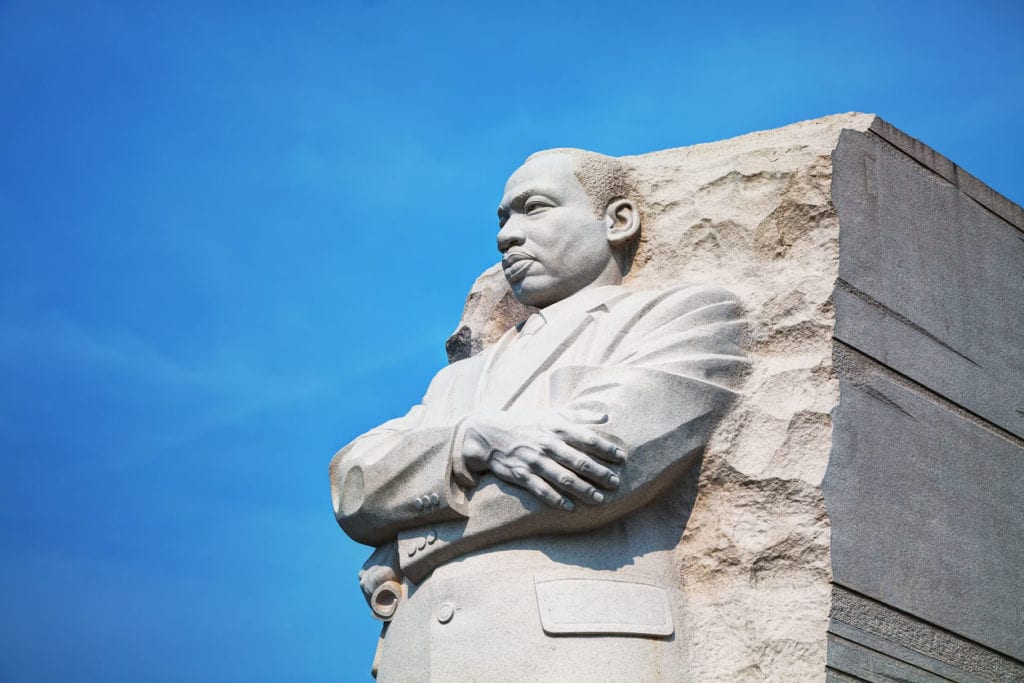

“Creative Maladjustment”: Refusing to Adjust to Injustice

We are re-sharing a piece written in January 2020 for Martin Luther King, Jr., Day. We took a look at King’s call to become “maladjusted” to injustice and shared research-based insights for being an “ethical champion” in your organization.

It is a great time to remind ourselves that “people who break with conformity aren’t doomed to a life of failure, frustration, and backlash. Rather, by employing the right strategies, ethical champions can not only speak up but also get others to listen and effect positive change.“

It takes courage to stand in front of a room full of psychologists and praise “maladjustment.” But that is precisely what Martin Luther King, Jr., did in 1967 when he delivered a keynote address at the American Psychological Association. On the one hand, King praised psychologists for fighting “destructive maladjustment” that could result in “neurotic and schizophrenic personalities.” But he also insisted there was something positive in maladjustment, something psychologists tend to overlook.

“There are some things concerning which” he said, “we must always be maladjusted if we are to be people of goodwill.” He mentioned racism, bigotry, economic inequality, and violence as realities “to which we should never be adjusted.” He declared, “Our world is in dire need of a new organization, the International Association for the Advancement of Creative Maladjustment,” and he called on his hearers to become like the prophet Amos, like Thomas Jefferson, and like Abraham Lincoln, all of whom, he said, were creatively maladjusted to the injustices of their day. “Through such creative maladjustment,” King concluded, “we may be able to emerge from the bleak and desolate midnight of man’s inhumanity to man, into the bright and glittering daybreak of freedom and justice.”

What Keeps Us Complacent?: The Science of Moral Disengagement

King, of course, did not live to see the ways psychology would grow and develop over the remainder of the 20th century. (He was assassinated just seven months after his address to the APA.) But he no doubt would have appreciated the work of social psychologist Albert Bandura, who described eight “mechanisms of moral disengagement,” or processes by which we grow complacent and callous to the immoral behavior around us. They are as follows:

1 – Justification – We construe unethical actions as serving some important social or moral purpose.

2 – Comparison – We compare unethical actions to others’ even worse behaviors.

3 – Euphemisms – We make actions seem less immoral by using doublespeak and sanitizing language.

4 and 5 – Displacement or diffusion of responsibility – We deny or minimize our role in wrongdoing.

6 – Denying injurious effects – We place the effects of unethical actions out of sight and out of mind so we do not have to be accountable for them.

7 and 8 – Dehumanization and attribution of blame – We see victims as not worthy of protection or blame them for bringing harm on themselves.

We can see these mechanisms working in our own lives when we hesitate to voice our values at work or in our communities. But Bandura’s larger point was also that groups engage in them and perpetuate “large-scale inhumanities” like the social problems King had in mind.

Social psychologists like Bandura provided excellent descriptions of what can keep us quiet and complacent. In fact, research has emphasized the power of conformity and complacency in the face of injustice. It has sometimes suggested that not only will the person who speaks up and champion ethics in their context struggle to convince others, he or she may also face negative consequences, facing ostracism or outright punishment for daring to challenge the consensus. We might conclude from this work that “creative maladjustment” won’t work; people who try to create change will fail and get hurt trying.

Effective Ethical Champions: New Research on What Works in Challenging Moral Complacency

Fortunately, recent research is exploring ideas like “creative maladjustment” more seriously. Penn State researchers Anjier Chen, Linda Treviño, and Stephen Humphrey recently investigated what happens when an “ethical champion” challenges unethical behavior in a team setting. Teams were asked to make a recommendation for a start-up that lower costs yet cause potential harm. They planted “ethical champions” (actors) in each team, and analyzed the video of these discussions to learn how ethical champions might influence the team’s ethical decision-making.

They discovered that ethical champions were surprisingly effective. And they found that in addition the actors who acted as ethical champions, other team members often emerged as ethical champions. Both types of champions were effective in: 1.) Raising the team’s awareness of ethics issues; 2.) Helping the team avoid the mechanisms of moral disengagement; and 3.) Pointing out the business case for taking ethical action.

What emerges from their work is not just the message that you can be effective in making change as a “creatively maladjusted” person, but also a set of practical ideas for doing so in your everyday life.

Put it in practice

What are the strategies “creatively maladjusted” individuals can use to challenge complacency and moral disengagement?

1. Focus on framing.

Chen and her colleagues found that those who spoke up to challenge the consensus did so by re-framing the decision. Rather than simply approaching the decision with a “business frame” (i.e. “How much will this cost?” or “How much do we stand to profit from this decision?”), they focused primarily on the harm done to people. Chen and her colleagues also found that ethical champions could be effective when they focused on the business case for doing the right thing—for example by pointing out the threat of lawsuits, boycotts, or damage to the company’s reputation or brand. But focusing only on the business case for doing the right thing had a weaker, more short-term effect than when ethical champions spoke directly about ethical concerns.

2. Channel anger constructively when speaking up.

Chen and colleagues found that the type of emotion we display as ethical champions influences how we are seen by others. They found that anger tended to backfire by making the ethical champion seem less likable and more threatening. Those who expressed sympathy, however, didn’t face the same consequences. While anger can be helpful and natural in the process of speaking up, it can also take on destructive forms. Martin Luther King, Jr., set a powerful example in this regard. He was well acquainted with anger, and he also had “a kind of genius for turning it into positive action.”

3. Be an ethics champion—or assign one.

We often select people for teams without ethics in mind. Instead, we focus on people we find likable or agreeable. But you need principled people as well. Chen and her colleagues suggest actually assigning a person to raise ethics issues and maintain a focus on ethics throughout the decision-making process. Not only does this ensure that the issues are raised, it also can remove some of the concerns and fears that a potential ethical champion might feel when speaking up.

There is much more work to be done on “creative maladjustment.” But Chen and her colleagues provide powerful evidence that people who break with conformity aren’t doomed to a life of failure, frustration, and backlash. Rather, by employing the right strategies, ethical champions can not only speak up but also get others to listen and effect positive change.

Originally published by ethicalleadership.nd.edu in January 2020.

June 3, 2020